Classics Museum

The Classics Museum, located on level 5 of the Old Kirk building on the Kelburn campus, houses a small collection of antiquities, mostly Greek and Roman.

The earliest objects we have are a flint and sherds from the Neolithic period (6000-3000 BCE, not currently on display); the latest are Roman coins and objects from around the 6th century CE. It includes holdings primarily of Greek, Roman, and Etruscan artefacts. The collection predominantly consists of vases and terracottas, but also includes objects in stone, glass, bronze and other metals. It was conceived, and continues to be developed, as a teaching collection.

Some objects have been purchased by the Classics programme, while others are on loan from the British Museum, National Museum of Athens, or private owners.

When not in use for teaching or other university purposes, the Classics Museum is open to the public for free visits during office hours on weekdays. We also welcome school groups and offer free tours. For information please contact the Curator, Diana Burton.

The Museum's online catalogue is currently under construction; in the meantime, a gallery of images of the Museum's holdings is available. Please contact Diana Burton with questions, corrections, or requests for other images or publishing permissions. Students from the Museum and Heritage Studies Masters Programme have written in more detail on some items in the collection.

The David Carson-Parker collection

The David Carson-Parker collection was donated to Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington’s Classics Museum in 2015, by Jeremy Commons, whose late partner David Carson-Parker brought them to New Zealand from Syria in the 1970s.

The collection consists of 70 ancient artefacts including glassware and pottery mostly from the Mediterranean and dating from the seventh century BCE to the sixth century CE.

Other artefacts

Our latest acquisitions, made in 2018, are a Tanagra figurine and an Etruscan mirror. The figurine is a terracotta of a woman standing in a relaxed pose with one hand on her hip, the folds of her clothing wrapped elegantly around her. Traces of paint remain. The mirror is bronze, with a bone handle; the back of it is engraved with the figures of the Dioscuri, the twins Castor and Pollux, leaning on their spears and facing each other.

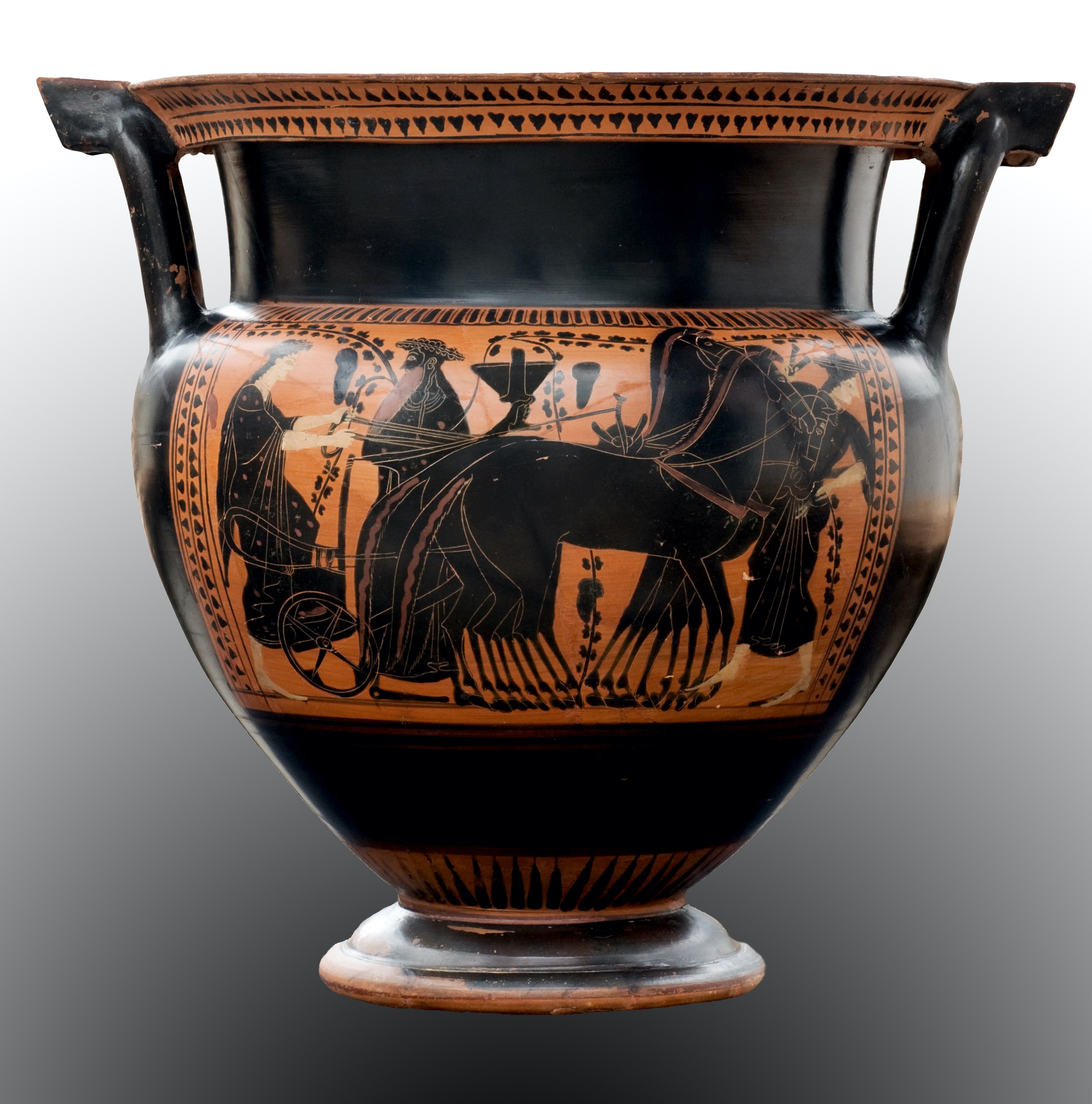

There is a considerable number of Greek vases, including some from Cyprus, Boeotia, and Corinth, and selection of Athenian vases from the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. Many of these were for use in the symposium, in which wine drinking became an elaborate social ritual. Among the most impressive of these is a large black-figure krater, for mixing wine and water, by the Leagros Group, from c. 520-500 BCE. On one side, it shows Dionysos escorting his mother Semele to be immortalised on Olympus. She steps into a four-horse chariot, ready to set off. In front of the chariot a maenad dances, accompanying herself with krotala (castanets). The other side is more sombre: three warriors farewell their families before setting off for battle. One is in conversation with his father, two with their wives; the woman in the centre holds a wreath, perhaps indicating that she is a recent bride. There are also two smaller red-figure kraters from South Italy dating to the fourth century BCE. One depicts Dionysos, this time as a god of the theatre holding a tragic mask; the other shows a satyr and maenad.

The Museum also holds a number of kylikes (wine cups), mostly in clay, but one in bronze. One of these, a Little Master cup from the mid-sixth century BCE, shows two satyrs, the half man, half animal followers of Dionysus, chasing each other around the outside. They look shaggier and altogether more wild than the one on the krater. The cup is finely made and the paintings tiny and detailed. As with the depictions of Dionysos and his followers on the kraters, so here too the choice of subject is appropriate to the function of the cup.

Other vases also depict mythical scenes, including another kylix showing Heracles wrestling the Nemean Lion, an olpe (jug) showing a Greek defeating an Amazon in battle, and a red-figure oinochoe depicting Athena extending her hand to a goose. The exact significance of this scene is not certain, but it may reflect Athena’s role as a goddess who cares for the prosperity of the household.

Among the Etruscan holdings is an Etruscan antefix. This example dates to the late 6th-early 5th century (approx. 515-485) BCE. This piece would have been attached to the edge of the roof of a temple or shrine. Its function was to keep the roof tiles in place, but it is also decorative. It shows the head of a grinning, bearded gorgon with goggling eyes and fangs, whose hair is represented by two archaic beaded black locks, which would be mirrored on the other side of the face, if complete. Gorgons were commonly represented in Etruscan art to ward off evil.

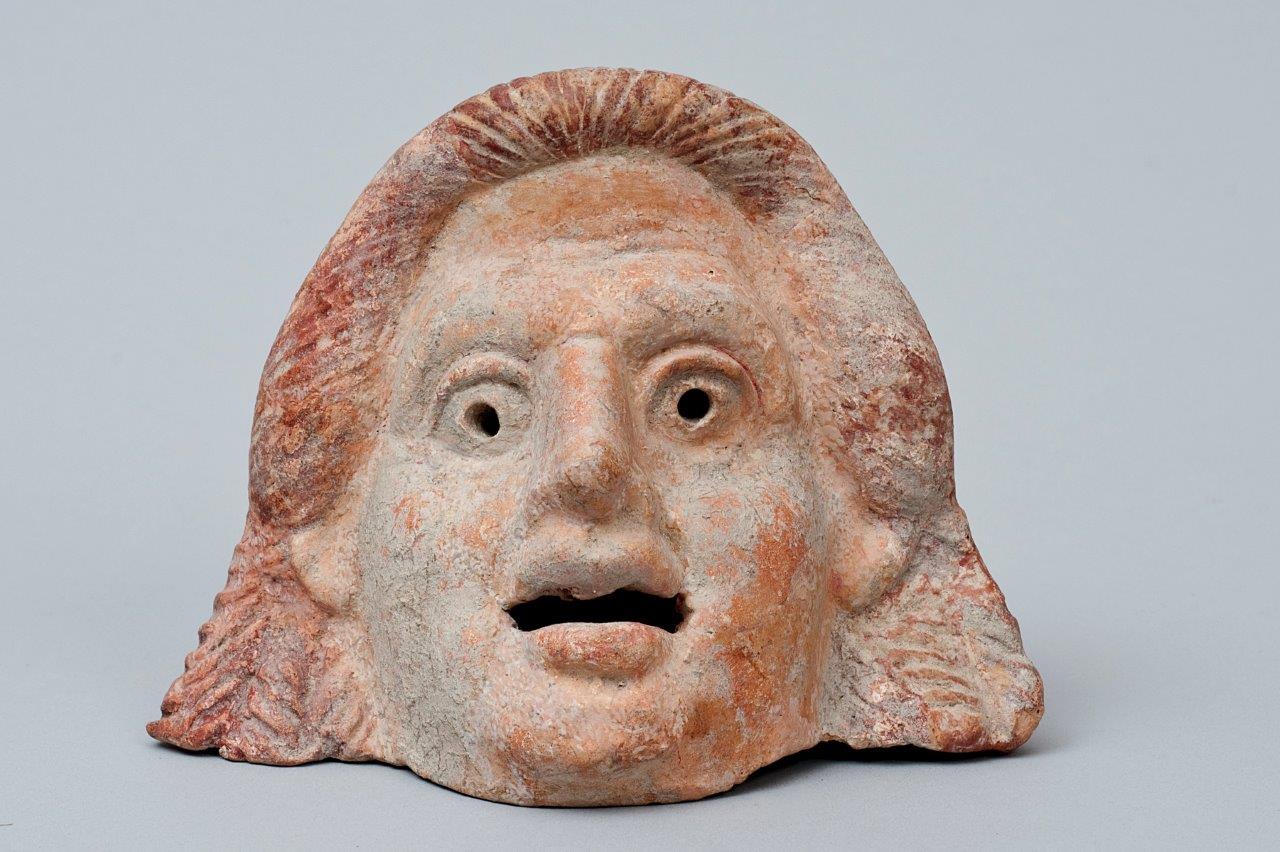

Another recent acquisition is a miniature Hellenistic theatrical mask of pinkish buff-brown terracotta, fired with some reddish-brown pigmentation apparently remaining in the hair. A complete work, the mask is typical of Pollux' category The Admirable Young Man, with pierced pupils and open mouth. It provides a striking three-dimensional example of theatrical headgear.

A Roman portrait head of a woman, probably from the eastern Mediterranean region, was acquired in 2003. It dates to the reign of the emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161 CE) or possibly into the mid-3rd century. Between her right eye and nose is a mole, an unusual individualising feature that suggests the portrait is of an actual person and not just an idealised woman. The marble used may have been imported from Attica. In provinces where marble was in short supply, the back and sides of a head might be pieced together, as that part of the statue would be less likely to be viewed closely. Hence, this head has been hollowed at the back in antiquity for the attachment of additional and separate pieces of the lady’s elaborate hairstyle.

The Museum also has a sizeable collection of coins, mostly Roman. Among them is a silver tetradrachm showing Cleopatra VII of Egypt. It was minted in Askalon in 50-49 BCE, and depicts the queen of Egypt as tough, capable, and determined.

The Museum also holds a number of miscellaneous objects such as a grave stele, transport amphora, fragments of wall painting, spindle whorls, a strigil, earrings, ship nails, and the like, as well as a small collection of fragments of papyri.