Using Google Earth to highlight environmental degradation

In 1972, Apollo 17 astronauts photographed Earth from 29,000 km away. The resulting so-called Blue Marble image helped galvanise the environmental movement, showing our planet as a fragile and interconnected system, explains Associate Professor Leon Gurevitch.

“Many astronauts have reported that national barriers make no sense when you’re up there in space,” says the design researcher, who is Associate Dean of Research and Innovation at Wellington Faculty of Architecture and Design Innovation. “It becomes obvious that what happens to one, happens to all.”

Associate Professor Gurevitch is working on a project that extends that idea of Earth as an interconnected system. Visualising Google Earth images in a game engine, Google Warming is an environmental and science communication project that helps make visible the sorts of environmental degradation that is often hidden out of sight.

“When you’re using a digital earth interface, you have a god’s eye view of the world and can go anywhere and do anything you want,” he says. “It encourages us to think of the Earth as an object than can be engineered, so looking at the kind of damage that has been done and trying to undo it can be seen as normal.

“I want to get a debate going about what geo-engineering is and how it might be done. There are all sorts of design ethics problems with it being unleashed without widespread public engagement regarding what it is and what the results might be.

“Much of the environmental change we enact upon the planet, be it geo-engineering to try to fix our problems or the more traditional environmental destruction we are used to thinking about, is difficult to tangibly experience or quantify.”

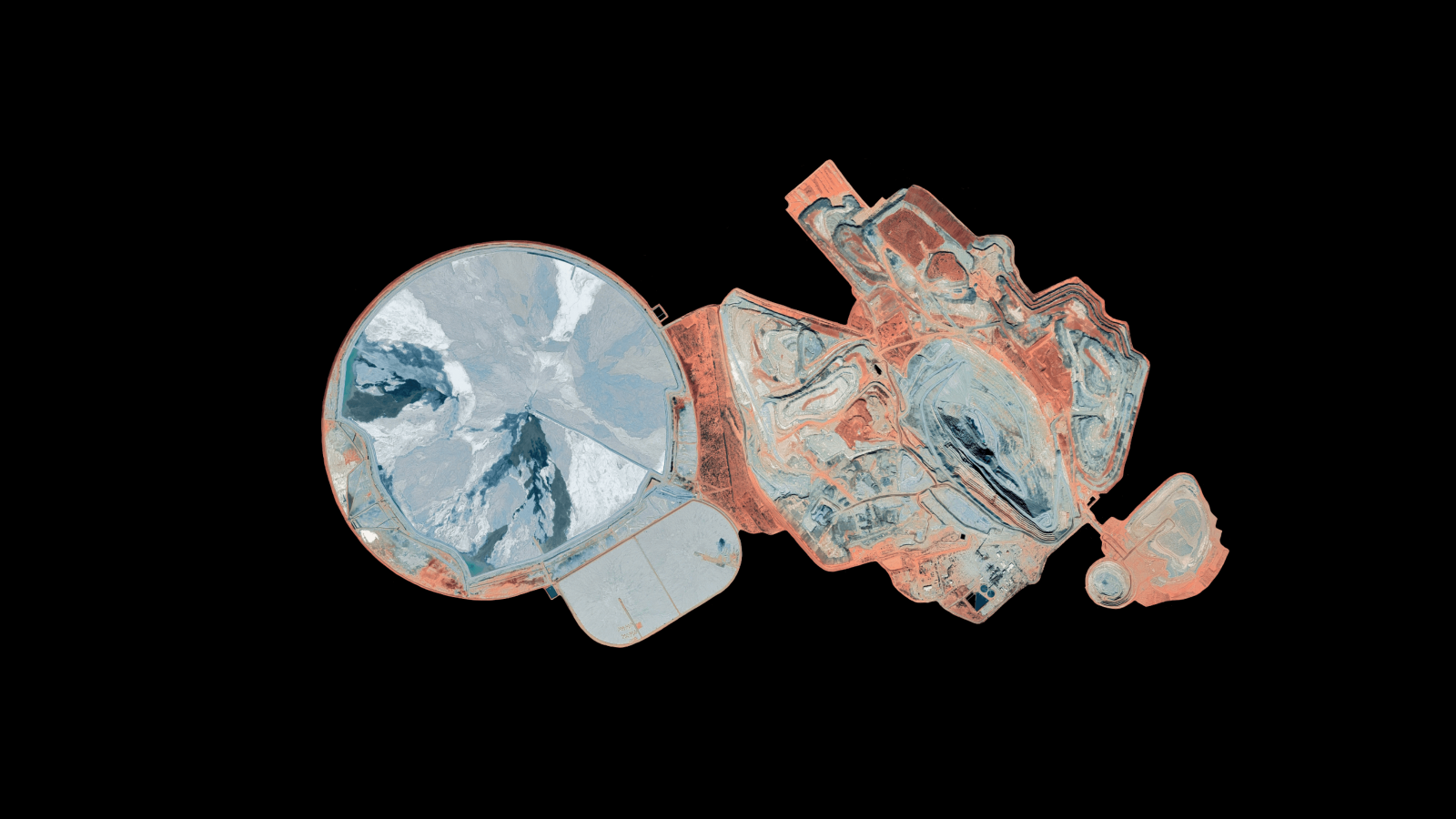

He says huge mines in Western Australia are an example of this.

“They are rarely visited and are often off the public radar. Taking the images from Google Earth and using a game engine to create an interactive image visualisation enables people to interact with them to understand their size and scale,” says Associate Professor Gurevitch.

“The lesson of environmental science and politics over the last 40 to 50 years is that government action often lags behind public opinion. The lesson for scientists is that, while for decades they may have felt they couldn’t be subjectively vocal about concerns because ‘science needs to be objective’, this approach is not tenable in face of cascading environmental degradation.”

Other visualisation projects Associate Professor Gurevitch would like to pursue include huge solar power fields in the Atacama desert, Appalachian mountain top removal in the United States, and deforestation in the Brazilian rainforests.

“I’m interested in large-scale visualisation and how we allocate resources on our planet. We have inadvertently wrecked our climate over the past 200 years. Imagine what we could do in 50 years if we were advertent about fixing it!

“My father always said that after World War II, we did what needed to be done. Nobody ran the numbers and said we couldn’t afford healthcare or welfare because that wasn’t the economic mindset of the war effort.

“After the war, that mindset continued; we built things like the National Health Service in the UK because it was the right thing to do. And you can compare that to what’s happening with the current pandemic—when we want to do what needs to be done, we can. The same approach needs to be taken with climate change now.

“We need to radically change the way we think about what we can do, and something like Google Warming can give the public more opportunity to engage and understand this.”

Associate Professor Gurevitch says that fixing the climate is sometimes described as being too difficult. In response, he suggests thinking about the vast scale of the current oil industry.

“We transport billions of tons of oil across the face of the planet every day; we extract carbon from miles below the ocean and from fields deep in the remote dessert. That doesn’t sound like a civilisation that could not do the same in reverse if we had the will to act.

“Our representation of the world and how we act upon it is not separate. Using tools like Google Earth—and what we can derive from it—means we have an entire generation thinking of the Earth as fragile but possibly also fixable. The biggest question is how do we start to fix it and who makes those decisions?”

Outputs of Associate Professor Gurevitch’s Google Warming project have included book chapters, research papers, public lectures and exhibitions featuring 3D printed models of damaged environments.