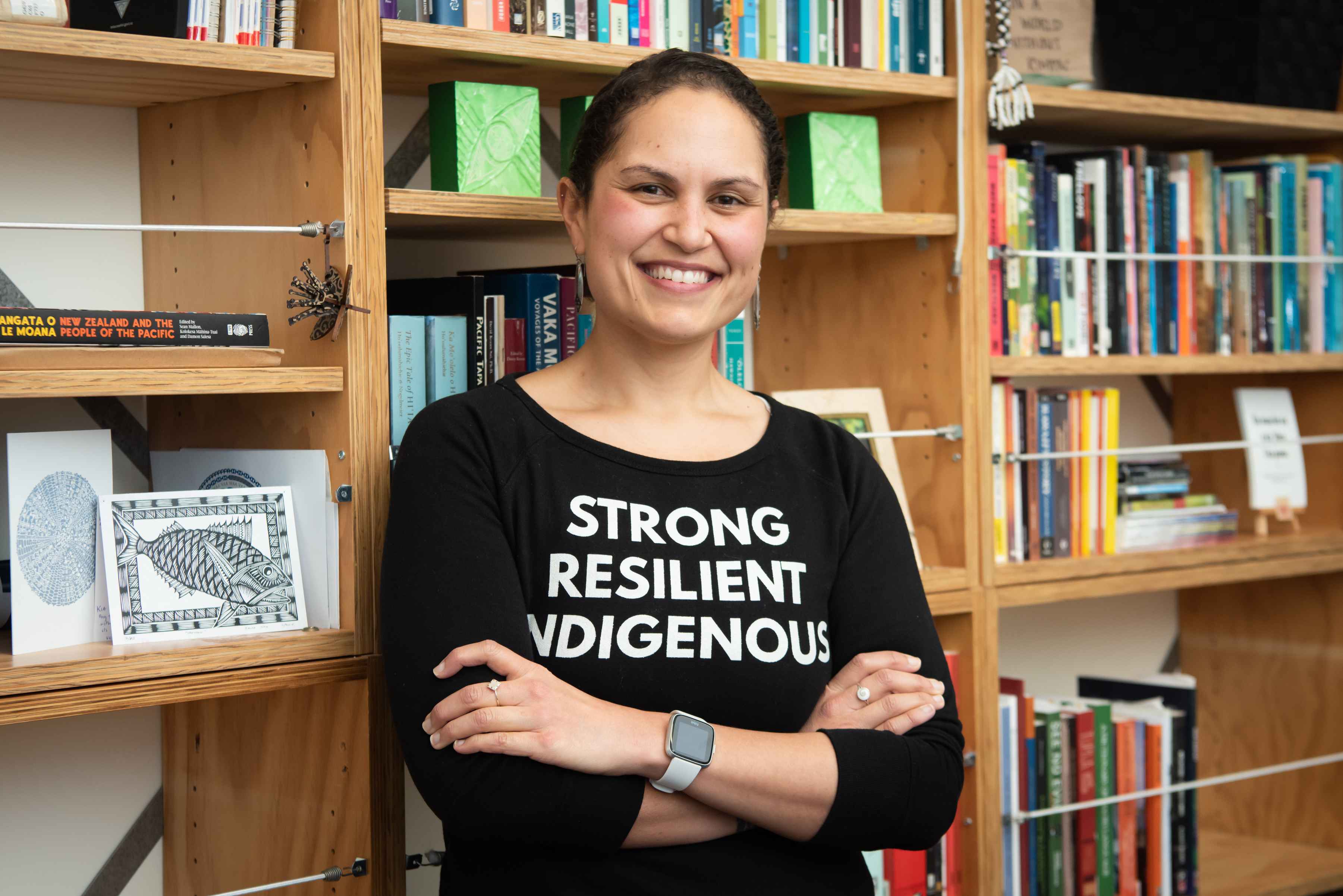

Pacific Studies lecturer Dr Emalani Case explains her passion for activism and teaching

Dr Emalani Case describes her activist roots and details some of the causes closest to her heart. She also discusses her current research and reveals how her passion for activism informs her work as a lecturer in Pacific Studies at the School of Languages and Cultures.

With seemingly boundless energy for advancing social, political and environmental causes, Dr Emalani Case is obviously someone with a very strong moral compass. She has worked tirelessly to highlight a multitude of issues and help make the voices of the downtrodden heard.

With seemingly boundless energy for advancing social, political and environmental causes, Dr Emalani Case is obviously someone with a very strong moral compass. She has worked tirelessly to highlight a multitude of issues and help make the voices of the downtrodden heard.

Most recently, for example, Emalani spoke to the crowd at the Black Lives Matter march in Wellington offering her fellow demonstrators support and guidance. She reminded those around her that "Radical change requires that we do the work... when the hashtag stops trending" and that "the real work happens every single day when no-one is looking.”

Emalani is an inspirational figure and is always generous in her support for others struggling for justice and change. She holds a particular affinity for fellow Indigenous peoples of Te moana nui a Kiwa (the Pacific) and sees a number of parallels in their experiences of colonialism as well as the current injustices they face. Last year, she demonstrated this solidarity when visiting the protectors at Ihumātao. At the same time, in her native Hawaiʻi, there are plans afoot to build an enormous telescope atop the 4,000m mountain, Mauna Kea. The telescope would desecrate the site considered sacred to the Hawaiian people.

Despite her very busy teaching schedule and preparing for Trimester 2 courses, she was kind enough to make time to answer some questions about herself and her work.

Can you tell us a little bit about your background?

I was born and raised in Hawaiʻi. Who I am as a Kanaka Maoli (Hawaiian) woman informs everything I do in life. When I came to Aotearoa in 2012 to work towards a PhD in Pacific Studies, it was my goal to study and deepen my connection to the larger region and to find my place in it. My coming back here to work as a lecturer is an extension of that goal. Now, though, it’s not necessarily about finding my place but about realising my genealogical responsibilities to the region and acting upon on them.

What courses do you teach?

I teach PASI 101 - The Pacific Heritage, PASI 201 - Comparative History in Polynesia, and PASI 301 - Framing the Pacific: Theorising Culture and Society.

Where did your passion for activism come from?

I’m not sure it’s a passion as much as it’s a responsibility. Born as an Indigenous person, I see it as my responsibility to be active in working towards bettering the lives of Indigenous people, at home in Hawaiʻi, here in Aotearoa, and in the wider Pacific.

That sense of responsibility comes from my upbringing. I was born in the wake of what’s referred to as the Hawaiian Renaissance. I was born at a time where Kānaka Maoli (Hawaiians) were reenergizing and reemerging, ready to tackle the colonial issues and legacies keeping our people down. I was born into this political context and was raised by parents who were (and continue to be) part of the movement. Therefore, I don’t think I had a choice of being an activist. The choice I had to make, however, and the choice I have to continue to make every day, is how I want to embody that activism in my daily life.

What are some of the causes closest to your heart?

There are so many movements that I’m passionate about and that feed and inform my activism. Here are a few that are close to my heart:

The movement to protect our mountain, Mauna Kea, in Hawaiʻi. To stand to protect our mountain is about so much more than protecting one place. Ultimately, it’s about protecting all sacred spaces, and in the process, also protecting the relationships Indigenous peoples have to those places.

The movement to demilitarize Hawaiʻi and to end the military occupation of our islands. To stand for demilitarization is to put an end to the ongoing destruction of our environments and to enable our people to grow and prosper in our own lands. To demilitarize is also to put an end to RIMPAC, the biennial maritime war games that take place in Hawaiʻi (a movement I am currently quite involved in).

The movement for a free and independent Pacific. To stand for a free Pacific is to support movements for justice and liberation in West Papua, for example, to stand against genocide, and to do what we can from here to speak for those who are not always heard.

The movement for climate justice. To stand for climate justice is to demand that the lives of those most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, many of which are in our region, have the freedom to live and grow in environments that are healthy.

Can you tell us about some of your current research?

A lot of my current research has to do with activism and solidarity. It has to do with exploring national and regional responsibilities and obligations to each other as Pacific peoples. It has to do with forging and strengthening relationships through critical analyses of those relationships, exploring their ruptures and then how we might go about mending them.

I’m currently working with the University of Hawaiʻi Press to publish my first book, Everything Ancient Was Once New: Indigenous Persistence from Hawaiʻi to Kahiki (due to be published in early 2021). It was inspired by the work I did for my PhD thesis, which focused on Kahiki, or the Hawaiian concept of an ancestral homeland in the Pacific. The book, however, brings Kahiki into the present to explore Indigenous persistence in various contexts in the region, looking at everything from rooted and routed histories and solidarities, to cultural loss and revitalisation, to trans-Indigenous networks, and even to dreaming and envisioning radically different futures for our Pacific.

How does activism inform your teaching?

My activism is motivated by my dreams for the Pacific. Those dreams inform the way I structure my classes, the way I teach them, and the radial hopes I hold for the students who I get to work with. I’m very honest with all of my students. Though my job description may list certain roles and responsibilities, I walk into every class knowing that I am obligated to use that space to make the region better. My ultimate goal, therefore, is to help students engage with the region in critical ways, no matter their background, and to then help them find their place in it and hopefully, in the process, to find the positive contributions they can make to the region.

In PASI 101, for example, I am intentional in structuring my class in a way that provides space and time for students to unpack the complex realities of Pacific life today, including the struggles and injustices experienced as a result of colonisation. I try to equip them with the language to articulate those experiences, and then in other classes, like PASI 301, with the tools to hopefully begin finding their voice and how they might use that voice to stand for the movements they feel most passionate about.

Wellington seems to have drawn you back from the tropical warmth of your home in Hawai'i. What is it you like about Wellington?

Te Whanganui-a-Tara challenges me. It’s like a friend I keep getting to know better every day that I live here, but a friend that doesn’t always make the relationship easy. I have to work at it. The more I learn about this place, though, the deeper my affection for it becomes. I’ve been quite interested in learning about all of the streams and waterways that exist under the city. It continues to perplex and bother me that we walk on water every day. I currently live on a street in the city that runs over a stream called Waikoukou. The fact that I can’t hear or see that stream, and that the stream had to be covered in order for the city I now live in to be here, is both heartbreaking and unsettling. That feeling of being unsettled, though, has been so generative for me while living here. It’s pushed me to explore my relationships and responsibilities to this place as someone who is not Māori. Though I miss the warmth of home and the familiarity of that relationship, I am thankful every day for the opportunity I have to live here and to learn from this whenua.

Dr Emalani Case is a member of the Va'aomanū Pasifika team which is part of the School of Languages and Cultures. She contributes to the Pacific Cultures and Languages programme at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington.

Article: Benjamin Swale