Three weeks into the 2023 New Zealand Social Media Study (NZSMS), 2,437 Facebook posts by political parties and their leaders have been analysed by Dr Mona Krewel, director of the Internet, Social Media and Politics Research Lab at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington, and her team. The posts were made in the period from 11 September to 1 October.

The researchers have dug into the data to find out which parties are using disinformation, the political tactics they’re employing, and the groups that disinformation posts are attacking.

Is disinformation on the rise?

Despite concerns disinformation on social media would increase during the 2023 election campaign, results show this hasn’t happened, says Dr Krewel.

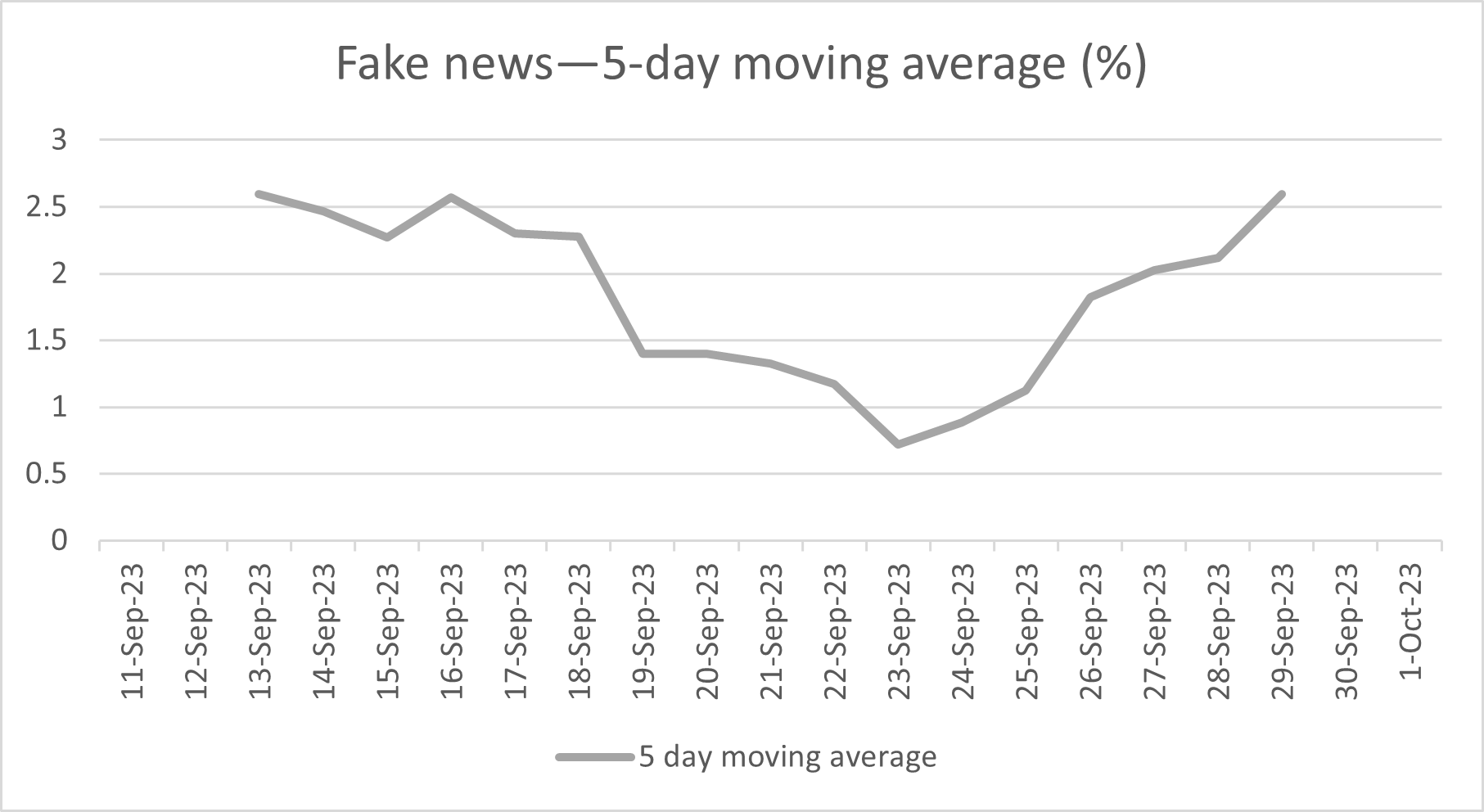

“Over the three weeks we’ve been monitoring Facebook posts, we have not seen an increase in fake news.[1] The fake news share of all posts in week three is roughly the same as it was in week one of the campaign. It peaked at about 2.5 percent in both week one and week three. In between, we even saw disinformation falling,” she says.

The proportion of fake news posts is similar to that seen in the 2020 election.

“This certainly is good news. When we monitored Facebook posts by parties and their leaders in the 2020 election, we found fake news was a peripheral phenomenon. Our results show the same is true this year.”

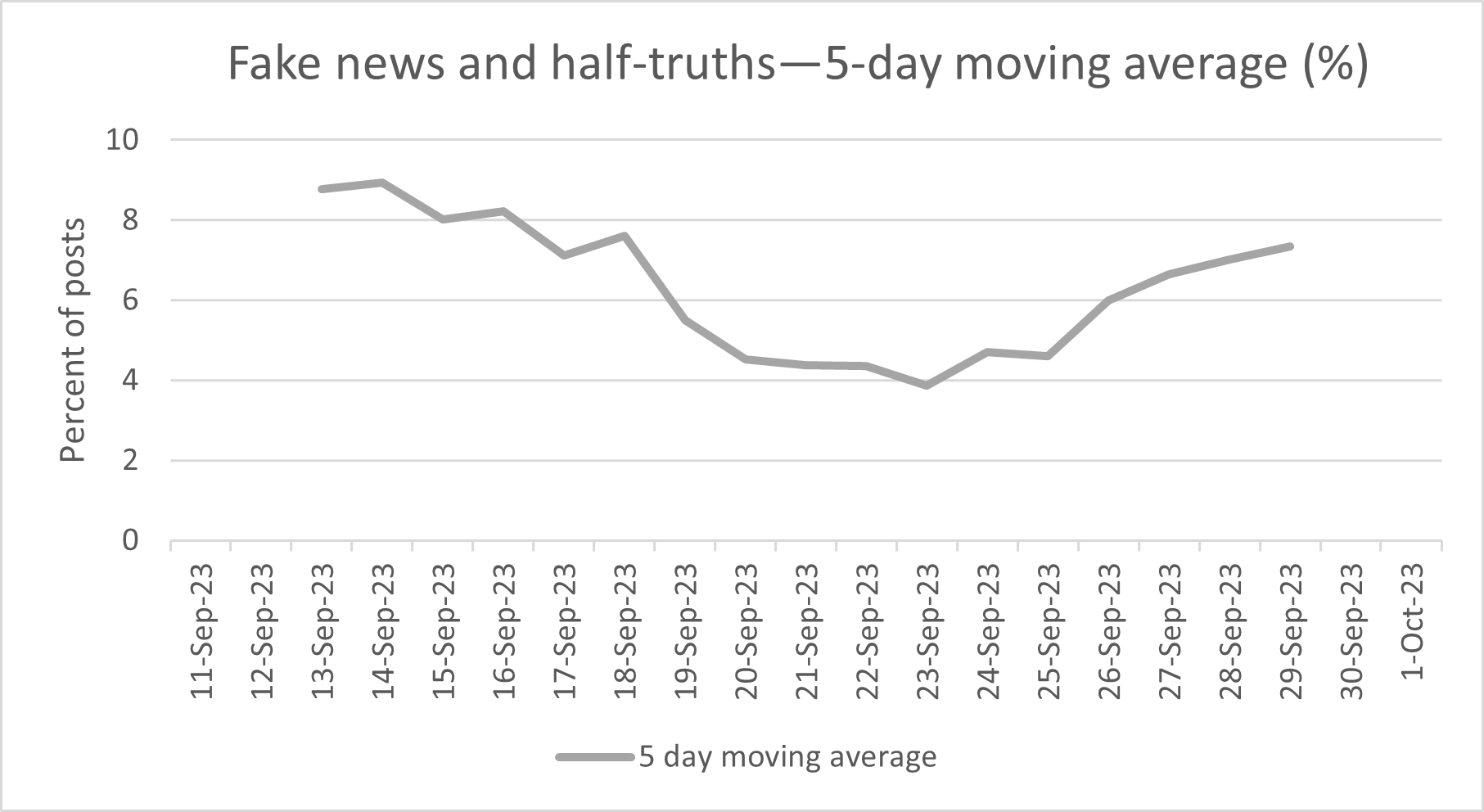

When posts containing “half-truths” are included in the mix, the proportion of disinformation posts rises though remains relatively low.[2]

“The share of disinformation posts—both fake news and half-truths—at no point exceeded nine percent of all Facebook posts in our sample. The parties are keeping it honest, for the most part. Disinformation even seemed to decline by week three compared with week one.”

Fake news was only found in posts by some “fringe parties” and not in posts by the parliamentary parties or their leaders, Dr Krewel says.

“We only found half-truths in posts from parliamentary parties. ACT and its leader David Seymour stood out here. ACT often states it is the only party that will implement a certain policy, thereby suggesting to voters something won’t get done if they don’t vote ACT. This is misleading as National and New Zealand First often advocate for the same or a similar policy.”

Attacking ‘elites’

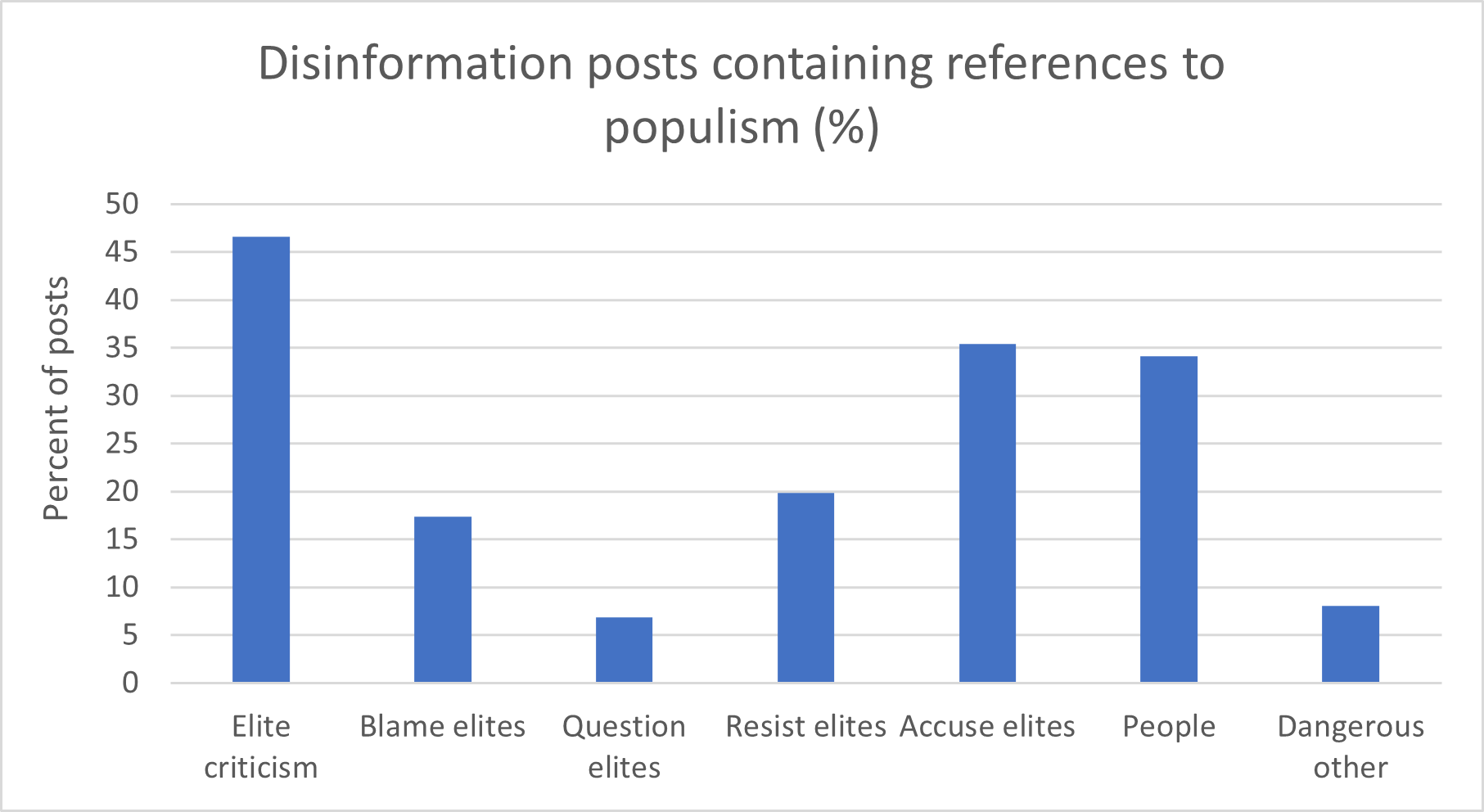

Many of the disinformation posts that the researchers identified used the “classic rhetoric” of populism, Dr Krewel says.

“Populist language is characterised by anti-elitism. Populists plot the people against the elites, which can be political elites, media elites, economic elites, bureaucratic elites, or even academic elites.

“Populists usually claim they are on the side of ordinary people against the elites by making ‘we, the people’ references. A core component of populist rhetoric is that it is anti-establishment,” she says.

Close to half of the disinformation posts in the sample contained criticisms of elites.

“Such posts present the people as a homogenous group of common men and women on the one hand and describe ‘the elites’ as an incompetent group of rulers on the other hand. About 35 percent of these posts accuse the elites of betraying ordinary New Zealanders. Nearly 20 percent also call for resistance against elites. That is populism in its purest form.”

Populism occurs on the left as well as on the right of the political spectrum, Dr Krewel says.

“However, left-wing populism is usually more inclusive and often makes strong redistributional claims. We typically find this type of populism in Latin America, while right-wing populism mostly occurs in Europe.

“Right-wing populism is more exclusionary and typically names ‘dangerous others’ such as outsiders or minority groups that—according to right-wing populists—must be perceived as a threat to the common people.”

The researchers found references to “dangerous others” in about eight percent of disinformation posts.

Topics of disinformation posts

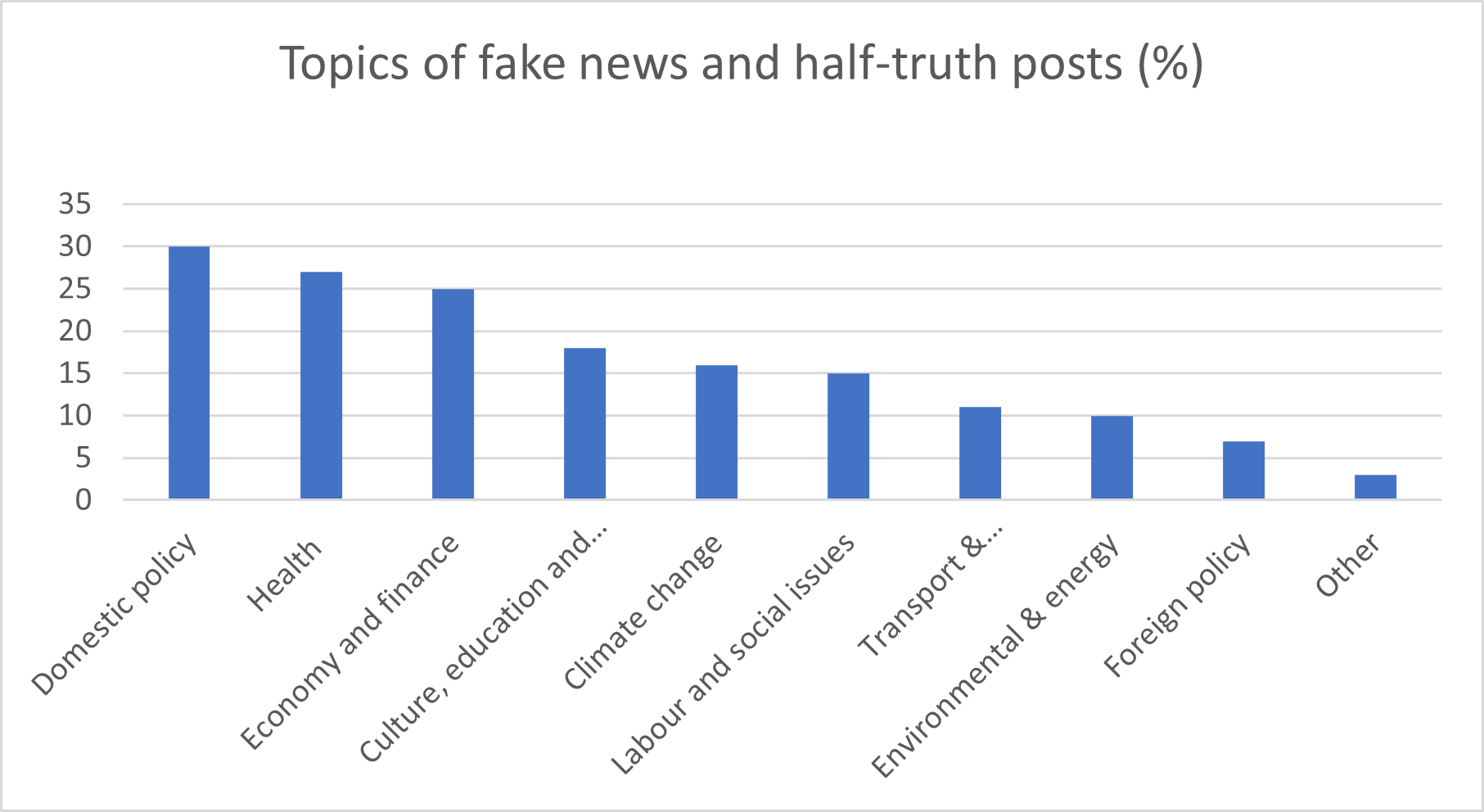

Thirty percent of disinformation posts focused on domestic policy issues, the most common topic.

"This largely reflects the number of posts containing half-truths—rather than full-fledged fake news—on domestic policy issues. An example is a half-truth post by ACT stating it would be the only party to get tough on crime and bring back three strikes, even though National is promising to do the same.”

Health policy was also a key focus of disinformation posts.

“This will probably surprise no one given the amount of disinformation we have seen about COVID and vaccination since the start of the pandemic. However, false health-related posts also extend to other topics, such as claims about adverse reactions to electromagnetic fields,” she says.

Conspiracy theorists have also broadened their agenda since the pandemic.

“The self-proclaimed freedom movements are not single-issue movements anymore. They have learned how ‘to surf the agenda’, as political communication scholars say, and figured out how to embrace new topics and give them their very own conspiracy framing.

“This is how these movements have managed to survive since the vaccine mandates were removed. Without adopting new topics, they would have lost their followers and died down.

“Their fake news posts appeal to emotions, oversimplify things, and directly jump to conclusions,” she says.

Targets of disinformation

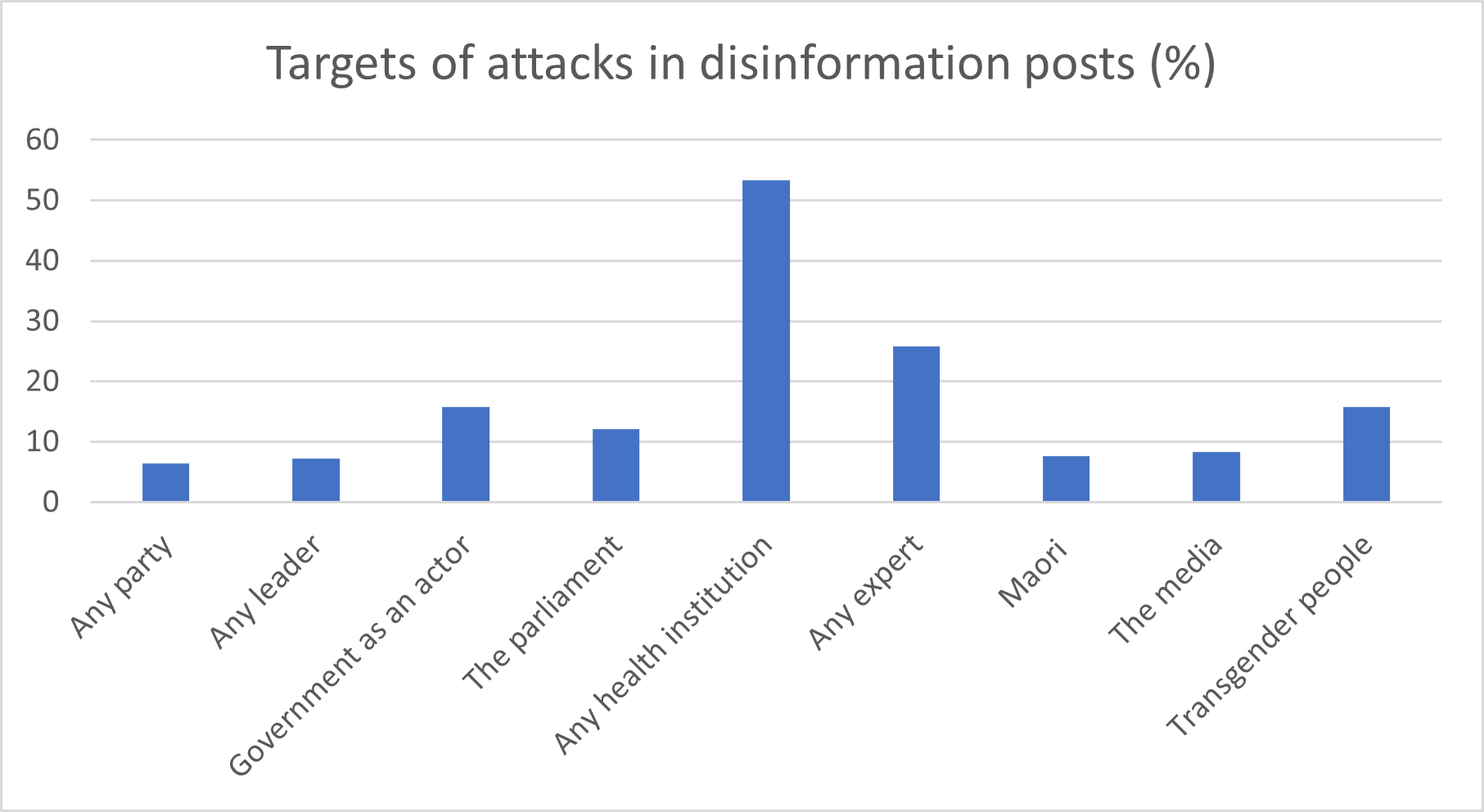

Almost 80 percent of disinformation posts attacked health institutions (53 percent) and experts (25 percent).

“These results show academics, who do science communication and provide the public with their expert knowledge, are often a bigger target of attacks than politicians these days,” Dr Krewel says.

Other targets of attack in disinformation posts included transgender people (15.8 percent of posts), the government (15.8 percent), the ‘mainstream’ media (8.4 percent), and Māori (7.7 percent).

“This tells us that we need to think more about how to protect these groups from disinformation on social media. This especially includes people in the health system, scientists, journalists, transgender people, and Māori.”

Dr Krewel says the optimism she voiced at the beginning of the campaign about the low volume of disinformation still holds.

“However, I am worried about the orchestrated attacks against specific groups in Aotearoa and how fringe parties have conquered new issue areas since the pandemic in which to spread disinformation. It would be a mistake to underestimate them.

“While the overall amount of disinformation in this election campaign is not high, we still need to carefully monitor what’s happening so we can react early when we see social media flooded with organised disinformation campaigns.

“We need to know what these posts are about, who they attack, and on which rhetorical strategies and arguments they rely.”

Notes

[1] Fake news, for the purpose of this study, in accordance with most academic literature on disinformation has been defined as completely or for the most part made up and intentionally and verifiably false posts to mislead citizens. The usual disagreements and accusations between political actors have not been coded as fake news. Coders were advised to fact-check each post carefully using reliable sources. In case of doubt or when they could not find unquestionable contrary information, they were advised to code the absence of fake news. The term fake news remained reserved for very clear and severe cases only. In acknowledgement of everyone’s right to freedom of speech, the project intentionally chooses to under- rather than overestimate the amount of disinformation on social media.

[2] Half-truths are defined as posts that are not entirely, or for the most part, made up, but they contain information of questionable factual accuracy.