Uptalk—the use of rising intonation that makes statements sound more like questions—has become a talking point, with plenty of disapproving commentary.

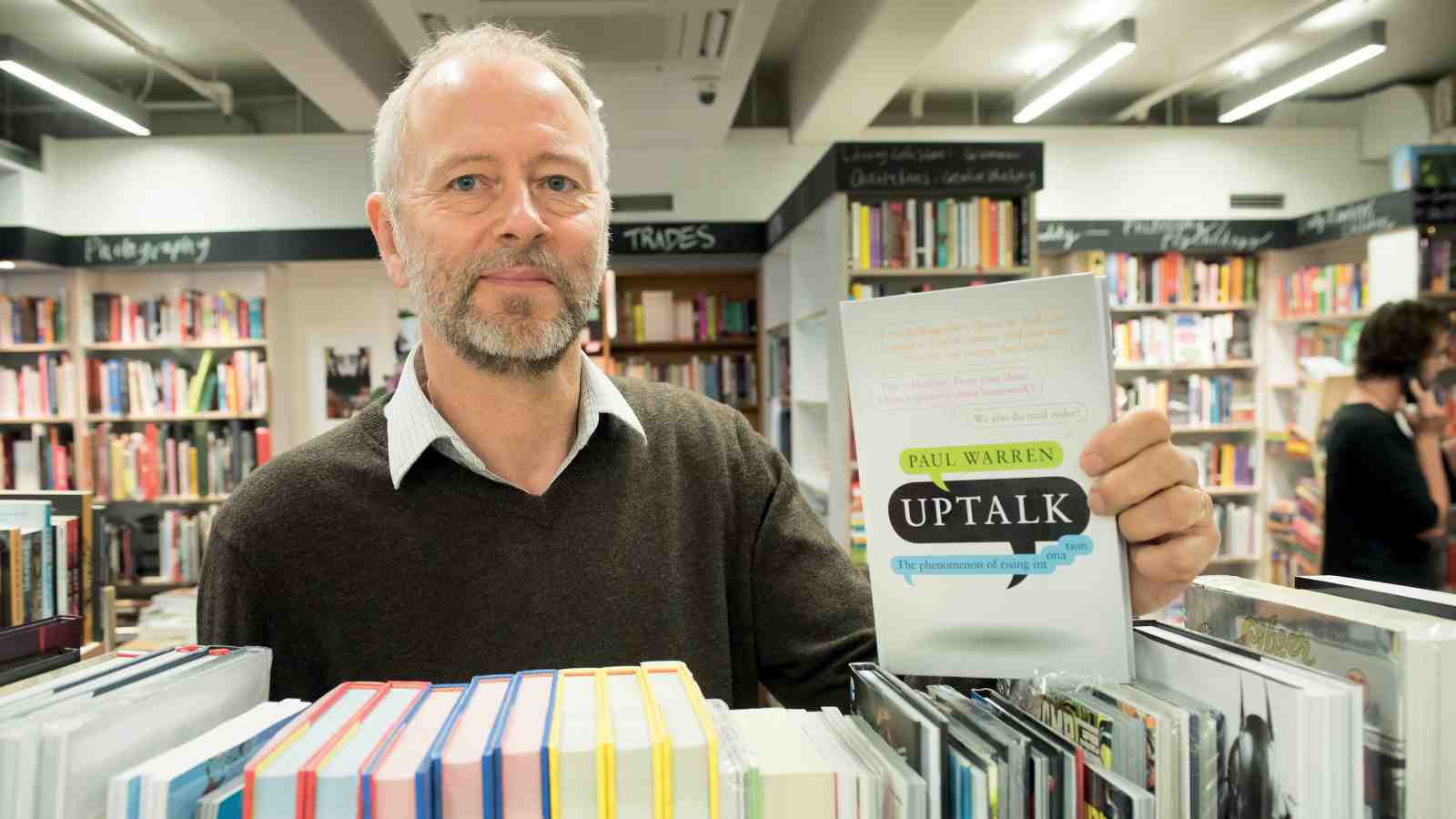

Now a new book, Uptalk, by Associate Professor Paul Warren of the School of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies brings together a wealth of research findings on uptalk from around the world. Uptalk is not only heard in New Zealand but also in Australia, Britain, Canada, the Caribbean, the Falkland Islands, South Africa and the United States. It is not limited to English and has been recorded, in a range of other languages including German, Greek and Japanese.

Paul’s book highlights that, while uptalk is more likely to be used by young women, recent studies show that there are male and older uptalkers too.

And rather than being used to indicate uncertainty, uptalk has been found to have a positive function of drawing listeners into a narrative or conversation. Recent research also suggests that the shape of the rise found in uptalk can differ from that found in questions, and that listeners are sensitive to such differences.

In New Zealand, research on uptalk in the 1990s and 2000s found it in use by Pākehā, Māori and Pacific peoples. One analysis of recordings from the 1940s suggests it might have been present in the speech of two people born in the late-nineteenth century. More recently, uptalk has been studied in courtroom interactions.

Paul says that, although there was little differentiation in the use of uptalk across classes in New Zealand, the situation was different for social stratifications in Australia.

“The lower working class is using it more than the upper working class, and they are using it more than the middle class—except for the men.

“For the men, there is an avoidance by the lower working class—it’s almost as though they know that this is something associated with their group and they want to avoid it.”

Paul said the purpose of uptalk is seen differently by those using it—the ‘in’ group—than by those hearing it—the ‘out’ group.

“The ‘in’ group is using it largely to keep the communication channel open, trying to invite the listener into the conversation.

“The ‘out’ group perceive it differently. Members of this group hear it as questioning the validity of what the speaker is saying and then interpret that as showing a lack of security, a lack of confidence in what the person is saying, which reflects badly on the speaker.”

Uptalk has been published by Cambridge University Press.

Read more about Uptalk on the linguistics.kiwi website.