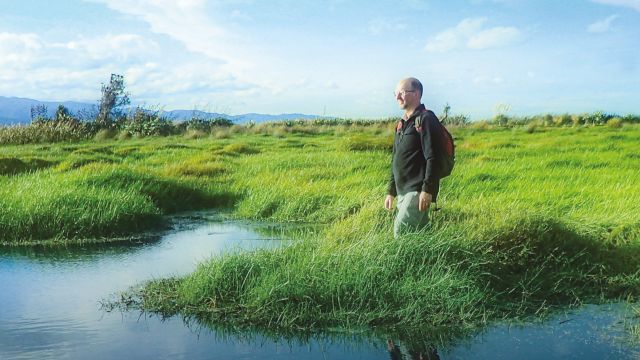

Today, the 132-hectare site is a mosaic of thriving wetland habitats thanks to a collaborative conservation project involving a team from Victoria University of Wellington, led by Associate Professor Stephen Hartley, director of the Centre for Biodiversity and Restoration Ecology in the School of Biological Sciences.

In 2011, Stephen was given free rein to carry out a large-scale field experiment to try to restore a kahikatea ‘swamp forest’—a forest that is inundated with freshwater, either permanently or seasonally—on the land.

Driven by a desire to test and improve habitat restoration, Stephen and postgraduate students from the University trialled five different techniques for suppressing tall fescue—an invasive grass species that smothers and prevents tree seedlings establishing. They planted a five-hectare block with 2,500 trees of eight species, including kahikatea, tōtara, mānuka, and ti kouka (cabbage tree), among others. “After eight years, many of the trees are well over three metres tall and setting their own seed,” says Stephen.

“Due to increased winter flooding of the area, not all of the original trees survive today. But regular monitoring of growth and survival has enabled us to gain a better understanding of each species’ environmental tolerances—how trees help each other, and which species to plant where in the remainder of Wairio,” he says.

“Now that the planted trees have the upper hand over tall fescue, a process of natural regeneration is starting to take hold. A large number of birds are using Wairio now. We have a variety of native ducks and black swans, and small flocks of royal spoonbill that have not been seen in this area for many years.”

The secretive and critically endangered Australasian bittern, or matuku, now call Wairio home too, and the hope is that their numbers will climb as the cover of reed bed—the matuku’s preferred breeding habitat—increases.

But the benefits of the restoration and the University’s involvement don’t end there. The rejuvenated wetland will play a key role in cleansing nutrient-rich water, which flows off surrounding farmland, before it enters Lake Wairarapa. Stephen also estimates that the restoration plantings have absorbed four to five tonnes of carbon so far—a figure that will increase exponentially over the coming years as growth of the larger trees accelerates.

The project, which was carried out in partnership with conservation group Ducks Unlimited New Zealand, the Department of Conservation, and the Greater Wellington Regional Council, has become a focal point for practical research and community collaboration, with other academics from the University’s Landscape Architecture, Science and Society, Geography, and Biological Sciences programmes developing transdisciplinary research and teaching links with the Wairio Wetland Restoration Trust and local Ngāti Kahungunu iwi.

Stephen says the project could also help to set the direction for future conversations about biodiversity in New Zealand.

“My hope is that our work here will inform future restoration activities, highlighting the important functions of wetlands and demonstrating the numerous gains that are possible when communities and researchers work together for sustainable and equitable futures.”