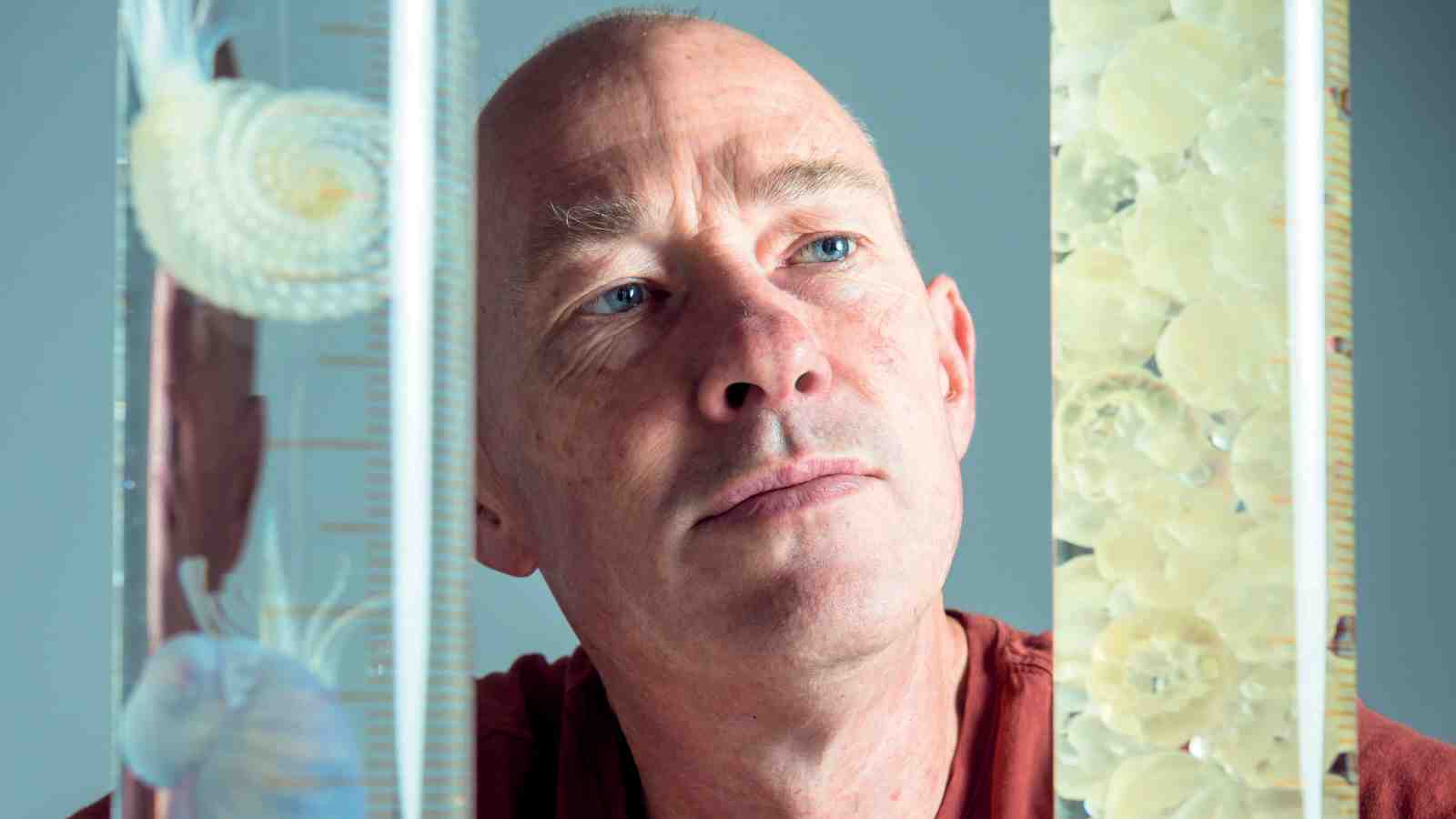

“I’m fascinated and a bit apprehensive of how objects made with computer code and 3D printers appear so similar to creatures grown with biological code—DNA.

“I know I’m onto something interesting when people’s first response is ‘that’s creepy’, because it’s just a bit too familiar.”

This technology isn’t new, says Ross, Victoria’s Industrial Design programme director—it’s been around for more than a decade.

“Victoria has been experimenting with 3D printing since 2006, when we purchased our first PolyJet printer.

“Many of our projects blur the line between living and fabricated. One of them, when immersed in water for a day, turned from transparent to white—and I remember being disappointed. But then I remembered human skin would turn white too if left in water for a day. That’s quite creepy when you think about it.”

And it’s only going to get creepier. The next step is 3D printing material that contains tissue and cells, says Ross.

“I think there’re a lot of big ethical questions around that. The question then becomes not can we, but should we? I’m really curious about what this means philosophically.”

Working with 3D printing is an exceptional educational tool, he says. “It helps students across many disciplines understand complex theories and prepare for the workforce.

“Software these days makes experimenting very easy—and with incredible results. Computer programs seem to take your ideas and turn them into something beyond what you’d originally considered, beyond what your constructive mind is thinking.

“One exchange student from the United States arrived in New Zealand having never done 3D printing before—and got access to the very latest equipment through our programme.”

The student’s project was made on the very latest machine from Stratasys—the world’s biggest manufacturer of 3D printers and 3D production systems.

Last year, in a New Zealand first, Victoria’s School of Design signed a research agreement with Stratasys. The University joined the Voxel Print Programme, an exclusive partnership with Stratasys Education that enhances the value of 3D printing as a powerful platform for experimentation on Stratasys PolyJet systems.

Experimenting on the PolyJet systems is an extraordinary opportunity for the University—and from a 3D printing perspective, this is the holy grail, says Ross.

“It is a bit like comparing all other 3D printing systems to a black and white television, and we have access to the first colour version. We’re one of only eight research groups in the world to have this.

“The beauty of this relationship is that we will also have access to Stratasys experts who will critique our research to make sure it’s in areas worth exploring and ones they haven’t yet explored. This means we will know we are undertaking relevant research that builds on the most current knowledge.

“It’s an exciting field and agreements like our one with Stratasys will make sure Victoria will play a world-leading role in this rapidly expanding industry.”