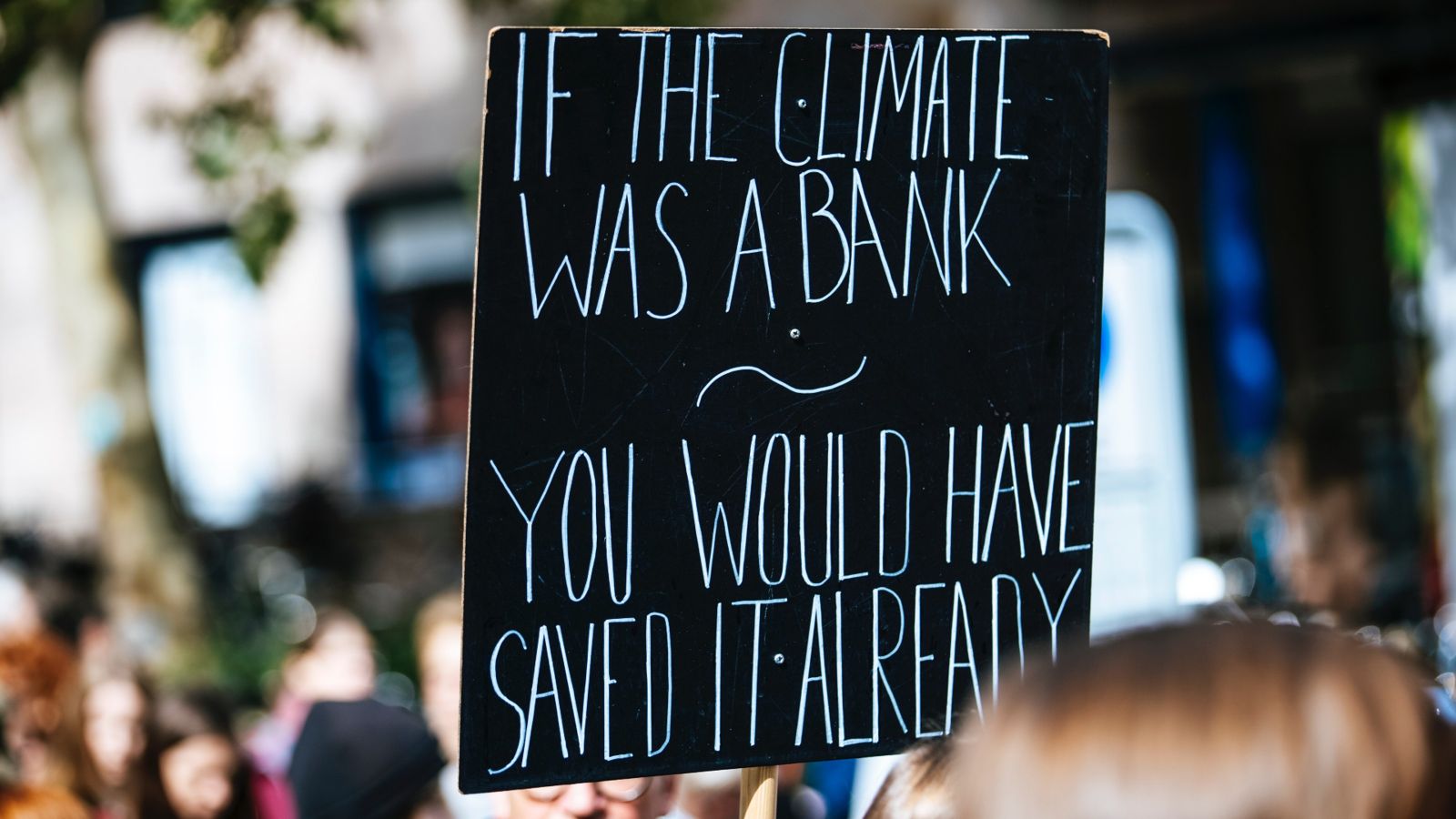

Comment: Young people took to the streets in the 2019 global climate strikes in possibly the world’s largest protest. Children and young people have continued to hold similar events, such as this year’s School Strike 4 Climate, calling attention to inadequate government responses to the climate crisis.

Some young climate activists—including 16-year-old Izzy Cook—have been the target of negative press and bullying as a result of their participation in these events. That’s unfortunate given their concerns about the need for urgent climate action are science-led and supported by strong evidence.

As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports make clear, we require a drastic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. However, global pledges are falling far short of what is needed.

An aim of the formal education system is to prepare children and young people for their (now unpredictable) futures. So, what are the key challenges for educators to address when it comes to the climate crisis?

It is important to affirm the validity of children and young people’s concerns regarding climate change and to affirm their climate grief and anxiety. This includes recognising the role of their activism in response to the slow and limited responses they see from adult decision makers.

However, our education system also needs to ensure students have access to effective and engaging climate education, including climate science, as well as mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Encouragingly, calls for climate change education were included in the government’s first national adaptation plan, Urutau, ka taurikura: Kia tū pakari a Aotearoa i ngā huringa āhuarangi. Adapt and thrive: Building a climate-resilient New Zealand.

Climate education has yet to be prioritised by the Ministry of Education. This is despite the many pleas not only from children and young people but the teachers’ union NZEI Te Riu Roa, and many teachers and schools across Aotearoa.

However, an effective climate change learning programme has already been developed and trialled in Aotearoa. This programme, Huringa Āhuarangi: whakareri mai kia haumaru āpōpō Climate Change: prepare today, live well tomorrow, is available free from the New Zealand Association for Environmental Education.

It supports educators and their students in Years 7-8 (ages 11 to 12) and is also relevant for Years 5-6 and 9-10. The eight modules cover topics from climate change science and Indigenous knowledge systems to critical thinking and communication.

Recently, a new climate wellbeing guide, Te Tai Unuora, was prepared to sit alongside these modules. This was developed after recommendations from focus group interviews with Pacific children and young people, high school climate activists, and rangatahi Māori.

In these discussions, young people demonstrated sophisticated analyses and critiques which underpin concerns for their future in the face of the climate crisis. They were aware of the connections between politics, economics, racism, colonisation, and ‘toxic masculinity’, as well as the dangers of social media.

Focus group participants considered Māori and Pacific worldviews to be key to addressing climate change, a view shared by other young climate activists. The role of Indigenous knowledge in providing effective climate responses has also been acknowledged by the IPCC.

Rangatahi Māori participants strongly felt the need to care for and connect to Papatūānuku, Tāne Mahuta, and Tangaroa, both as tūpuna and as crucial to wellbeing. These young Māori leaders positioned mātauranga Māori as a connector, as alive, as productive, and as hugely significant to Māori youth leadership, wellbeing and climate change.

The high school climate activists were very critical of individualistic ‘self-care’ approaches to wellbeing they had experienced in their schooling, recognising climate as a collective, existential crisis. One said:

"Self-care for climate isn't like self-care for … dealing with anxiety or depression or any kind of other mental health-related issue because it's not [an] individual issue, it is a collective issue. It is an issue that is about our connection with our environment, our connection with our planet, our connection with other people, and self-care is about connecting back to that environment. It’s about connecting back to the people and it's about building hope, building resilience and choosing to create hope."

As the late Māori Queen Dame Te Arikinui Te Atairangikaahu reminded us, we should listen more to children and offer them the same respect as adults.

Read the original article at Newsroom.

Jenny Ritchie is an associate professor in the School of Education at Te Herenga Waka Victoria—University of Wellington. She compiled Te Tai Unuora along with School of Education colleagues Associate Professor Mere Skerrett and Dr Ali Glasgow, and Associate Professor Sandy Morrison of the University of Waikato.