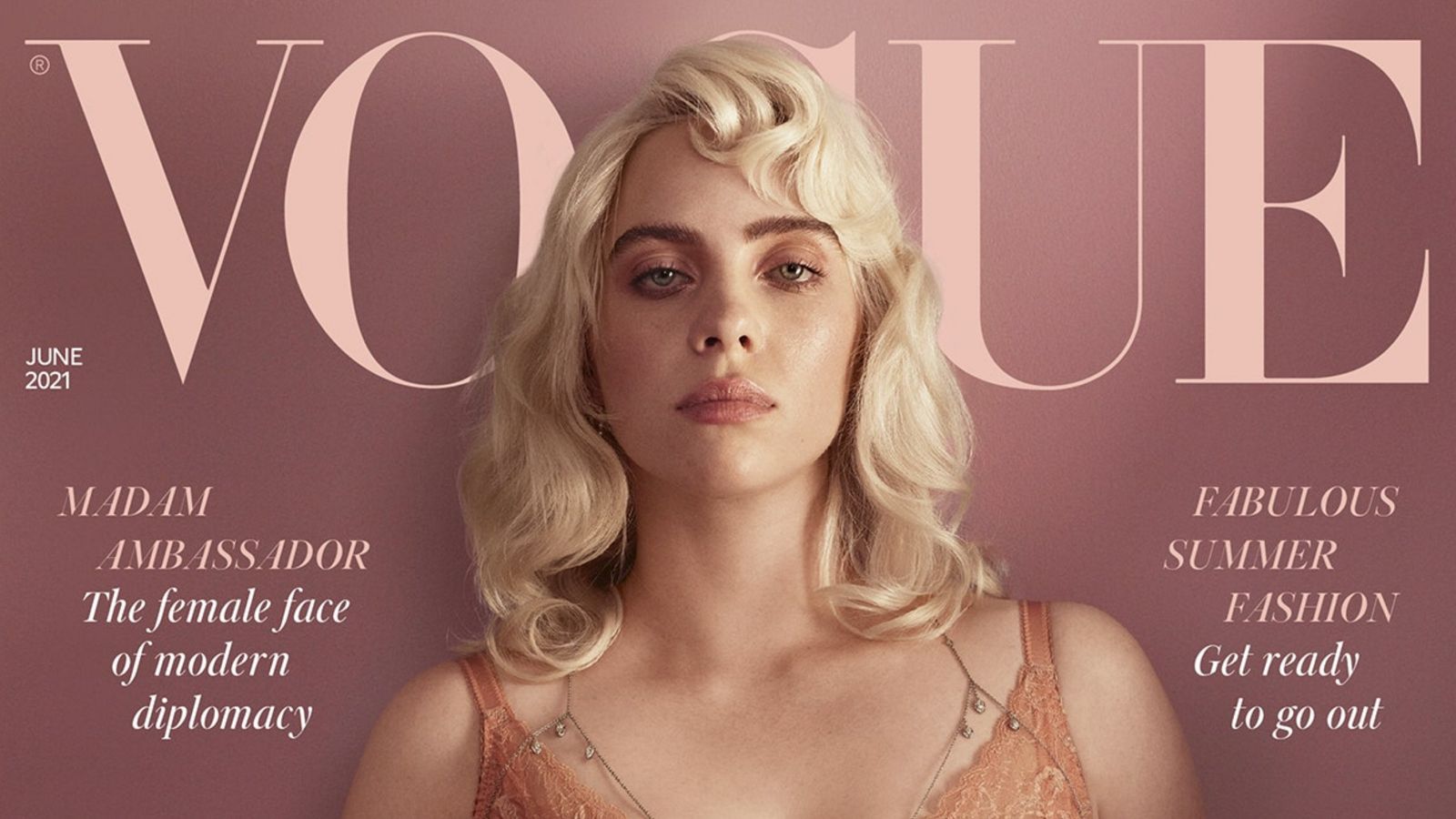

Singer Billie Eilish’s new look for British Vogue, in which she trades her baggy clothes for lingerie—most notably a series of corset— has sparked much debate.

Eilish has previously spoken of her choice to hide her body shape, and some saw the Vogue photo shoot as a sell-out or succumbing to patriarchal beauty standards.

In the article accompanying her Vogue cover, Eilish predicted such criticism, suggesting people would say: “If you’re about body positivity, why would you wear a corset? Why wouldn’t you show your actual body?”

But, she continued: “My thing is that I can do whatever I want.”

Corsets have long sparked debate. First worn by women in the seventeenth century, their form has changed over centuries. Throughout the eighteenth century, most stays (as they were then known) were in the shape of an inverted triangle—wider around the chest and narrowing in to the natural waist. Corsets were typically made of cotton, sometimes covered in a fabric like silk, and in the nineteenth century whalebone inserts were popular to create structure.

As the waistline of dresses rose through the Regency period, corsets changed to a straighter silhouette. When nineteenth century dresses were designed to highlight women’s natural curves, corsets changed also.

In the first half of the twentieth century, corsets were largely phased out as new styles of dress emerged, requiring less structure, and as new forms of undergarments became available. In her photo shoot, Eilish references mid-century pin-ups; corsets are now having a fashion moment, with a reported surge in online searches for them after the Vogue cover appeared.

The most enduring image of a corset-wearer is of an upper-class lady having the laces pulled tighter and tighter to appear beautiful and waifish for a ball. Given this, corsets are often viewed as a patriarchal symbol of female oppression and restriction, forced upon women to contort their body into aesthetically pleasing shapes—whether Kardashian curves or the “S” shape desired in the Edwardian era.

But women wore corsets while doing their daily chores: going to the market or helping with cooking or cleaning. Corsets had to be functional rather than restrictive.

Corsets are perhaps best thought of as a long-line bra. An everyday corset provided breast and back support. Rather than restricting women into certain forms, it provided support and the freedom to go about their day.

There were more structured corsets designed to be worn for balls and soirées. A little fancier, perhaps made of nicer material, and designed to be laced slightly tighter. But the lacing was not intended to cut off breath, and instead to create a pleasing silhouette.

While in a few cases corsets could have an effect on rib structure, these were extreme and a minority. Research has refuted “the longstanding medical belief that corseting was responsible for early death”. Most corsets were worn without incident.

Just as women today might wear shape wear for a night out, women of the past used corsets to make themselves feel more beautiful.

But interpreting this as women playing into patriarchal beauty standards strips these women of their agency. Women chose their own dresses, and the undergarments that went with them, and they decided how tight their corsets were laced.

Some of our misconceptions around corsets come from museums and television.

Corsets shown in museums are often laced to their tightest, and therefore smallest possible circumference, but they were more likely to be worn with space between the lacings.

Additionally, those corsets in museums are the ones that survived. Everyday corsets, suffering from normal wear and tear, were unlikely to last, so those still around today might be the fancier corsets, designed to look beautiful and thus smaller than average.

Television has also done us a disservice when it comes to corsets.

We have numerous scenes of women being laced far too tightly into their corsets, complaining of being unable to breathe, or even fainting from lack of breath (think of the Featheringtons in Bridgerton or Elizabeth Swann in Pirates of the Caribbean).

Often, actors are interviewed after taking part in a period piece and protest about how uncomfortable corsets were to wear and act in.

This discomfort was likely true, but not because the corset itself is the problem. Historically, corsets were individualised pieces of clothing, whereas corsets used for period dramas are less likely to be made specifically for an actress.

Describing corsets as “controversial” or “restrictive” reveals our modern views on items of the past.

It also points to much wider tensions in society—who do we dress for? How do we interpret body positivity?

At the end of the day, Billie Eilish is a young woman, experimenting with a new style, and that’s wholly her choice. And the corsets she wears have a long, expressive history.

Rachel Boddy is a PhD candidate in the History programme of Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington.

Read the original article on The Conversation.