Central Government Sector Pay – to freeze or not to freeze?

Dr Stephen Blumenfeld, CLEW's Director, discusses the Government's recent 'guidelines for wage bargaining' in central government agencies. The announcement, a de facto ‘pay freeze’ for public servants over the next three years - limited pay increases to those earning less than $60,000 a year, and those earning above that level up to $100,000 may be offered pay increases in some circumstances. But is there justification for such a "freeze" and what are the possible consequences?

The month of May has started out with two key – albeit seemingly paradoxical – announcements from the Government affecting workers’ pay. In the first week of the month, Minister for Workplace Relations and Safety Michael Wood revealed the Labour Government’s long-anticipated Fair Pay Agreements plan, which marks the first major transformation of New Zealand’s employment laws since the Employment Contracts Act was first enacted 30 years ago. That came on the heels of the Government’s announcement of a de facto ‘pay freeze’ for public servants over the next three years. While those earning less than $60,000 a year will see pay increases, and those earning above that level up to $100,000 will be offered pay increases in some circumstances, the Government intends there to be no increases for anyone earning above that level.

Finance Minister Grant Robertson asserted that the restraint on public sector pay was necessary to keep a lid on public debt, which rose steeply during the last year due to the Government’s efforts to lessen the economic impact of COVID-19 through measures such as the wage subsidy. After his meeting at Parliament the following week with the Council of Trade Unions (CTU), though, Public Service Minister Chris Hipkins seemed to backtrack somewhat on his earlier pronouncement, conceding that the pay ‘guidance’ – of which employers in the core public service must take heed - would be reviewed next year. He also offered his assurances that the Government remains committed to fast-tracking the pay equity and pay parity processes, the latter being a concern particularly in education, of which he is also Minister.

In announcing its new pay guidelines, the Government also indicated that it would still honour any pay increases previously agreed through collective bargaining and accruing over the next three years. The Government’s decision to keep public sector pay in check is, nevertheless, still likely to impact around three-quarter of employees in the sector, begging the question of whether a constraint on public service pay is warranted. In particular, there are several major central government collectives of between 2- and 3-years duration that are set to expire before the end of 2021. This includes twelve agreements, covering nearly 30,000 employees in the core public service and four CAs, with combined coverage of around 2200, covering Crown Research Institutes (CRIs) or State-owned Enterprises (SOEs). All of these agreements are set to expire and up for renegotiation in the next 8 months. Added to this is the fact that negotiations between the New Zealand Nurses Organisation (NZNO) and DHBs, which commenced in June last year, are ongoing, with 30,000 district health board nurses having voted to strike on June 9.

Remuneration rates in collective agreements are at the heart of bargaining and the renewal of any agreement. Some agreements in the past have had no rates included and the individual employee’s rate was agreed with the employer through the offer of employment, usually within a band of rates for the position offered. It is common that wage movements in collective agreements are indexed to external measures such as the CPI, the Labour Cost Index (LCI) and either the movement in the legislated minimum wage or a funding model. Nevertheless, as results of research undertaken by CLEW last year indicate, in the state sector, only 13 percent of collective agreements, covering only 7 percent of employees on collectives, have wage/salary movements related to such indices. Instead, most agreements in the State sector now specify a pay band or range of rates within which an employee’s pay will fall. Such clauses are typically included in agreements that prescribe a process for individuals to move through the bands and rates by promotion or high performance.

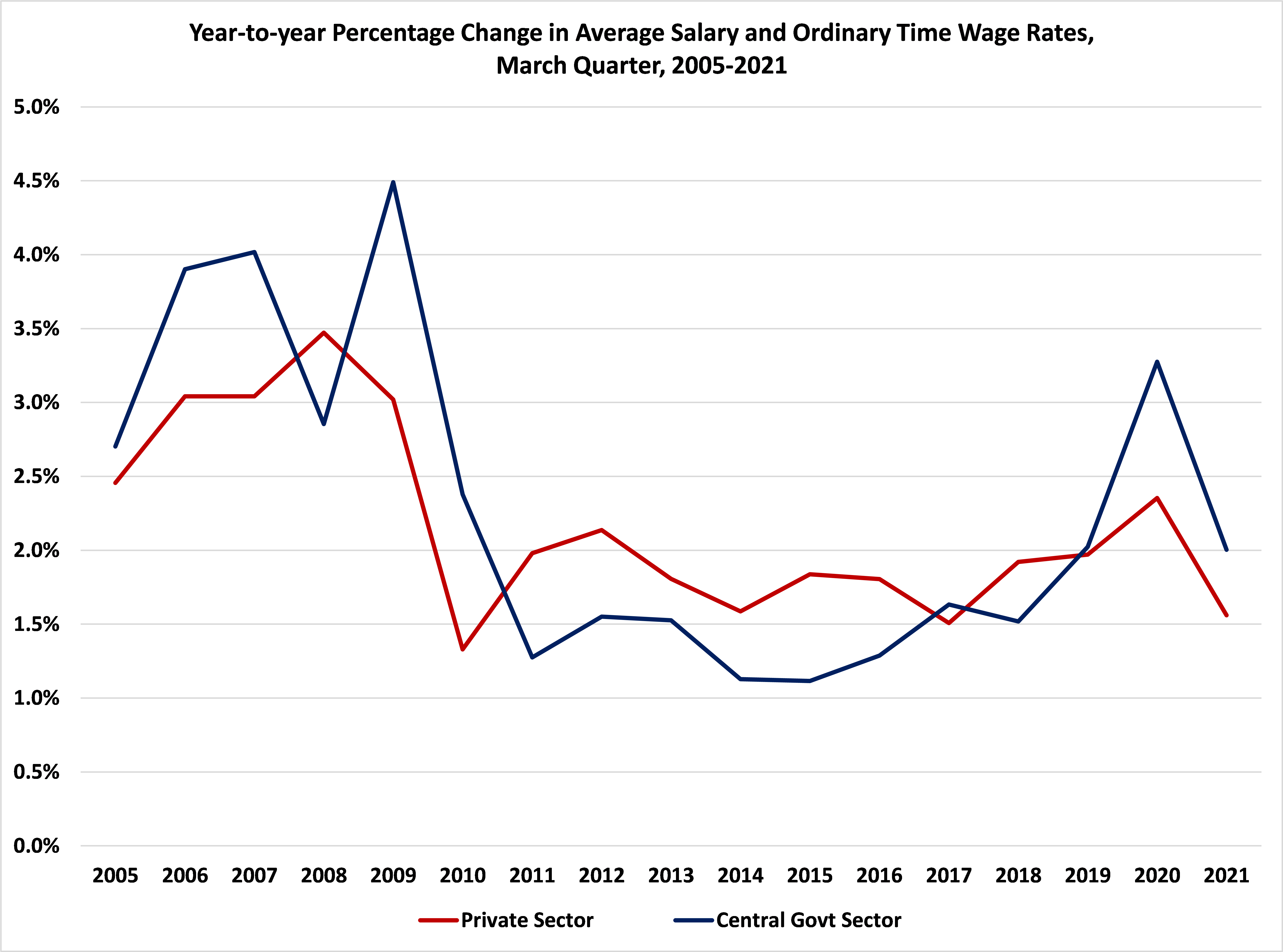

In addition, despite efforts to ensure that public sector workers are fairly compensated, central government employee’s pay often lags that of their private sector counterparts. As can be seen in the Figure below, this most commonly occurs under National Party governments, with central government employees typically catching up under Labour government. It is this latter point that raises a considerable element of surprise to the current Government’s recent announcement.

Statistics NZ, Table LCI027AA, and Table LCI025AA Quarter 1, 2004-2021.

This perception and the public sector wage restraint it engendered, as Jim Stanford has noted, hindered wage growth across Australia’s labour market – in both the public and private sectors – during the economic recovery following the 2008/2009 Global Financial Crisis. In a recent article appearing on the Centre for Future Work’s website, Stanford, Director of the Centre; also contends that more than a third of what are claimed to be ‘savings’ accruing from a public sector pay freeze is offset by the loss in revenue which would otherwise have come from taxing either the income or the spending by public servants.

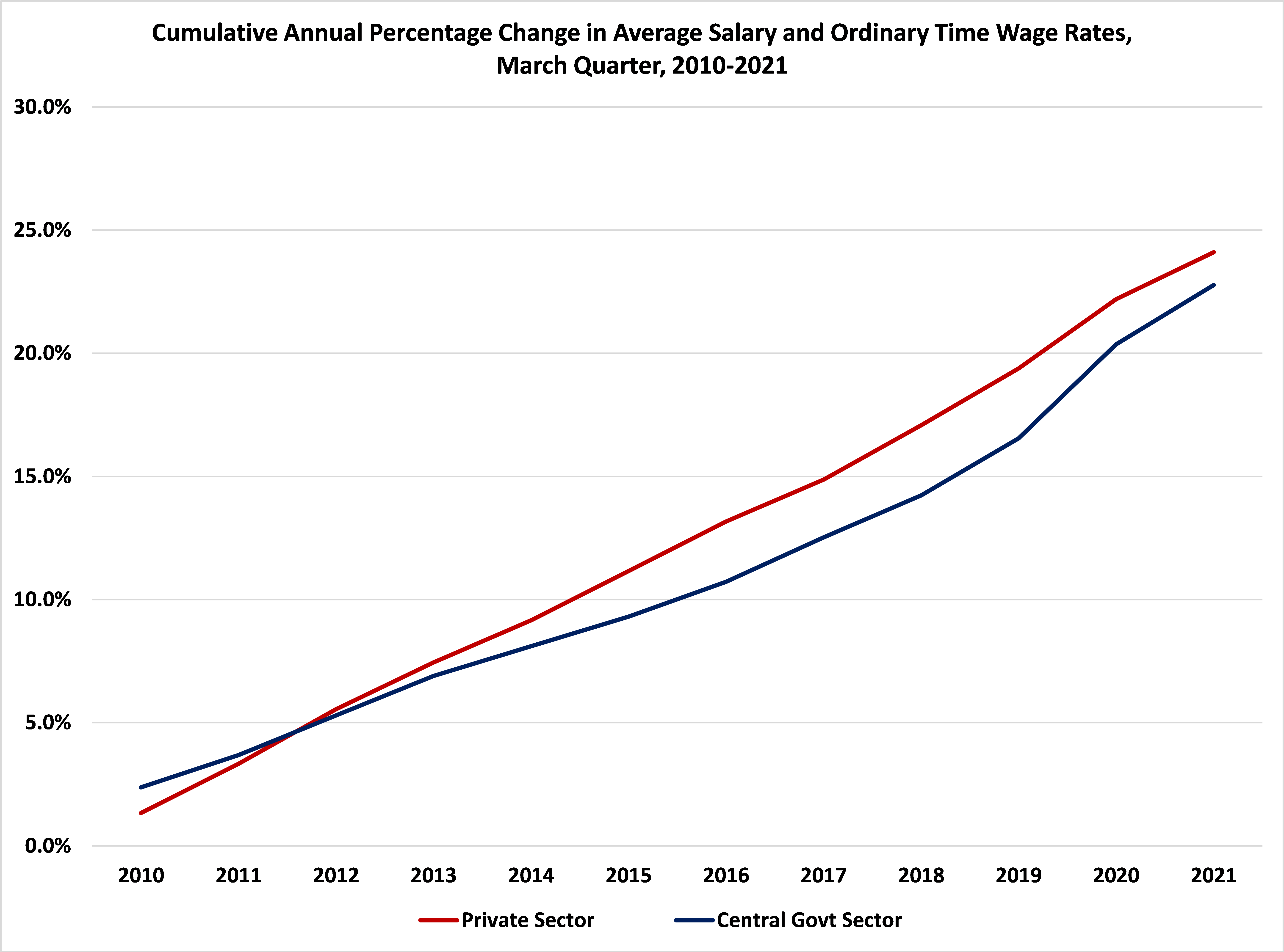

Finally, added to this is the fact that, contrary to what many in the media and general public seem to accept as fact, it is not the case that public servants – in particular those employed in central government – have fared better over time than their counterparts in the private sector. This is clear when one considers the cumulative effect of pay increases of both central government employees versus that of workers in the private sector over time. As can be seen in the figure below, the former have consistently lagged behind the latter over the past 12 years, which further highlights the inequity of any pay freeze affecting public servants, regardless of how long that effective ‘nil wage order’ is intended to last.

Statistics NZ, Table LCI027AA and Table LCI2025AA, Quarter 1, 2009-2021.