Meet our researchers

Find out about the leading researchers based in our Faculty.

Featured researchers

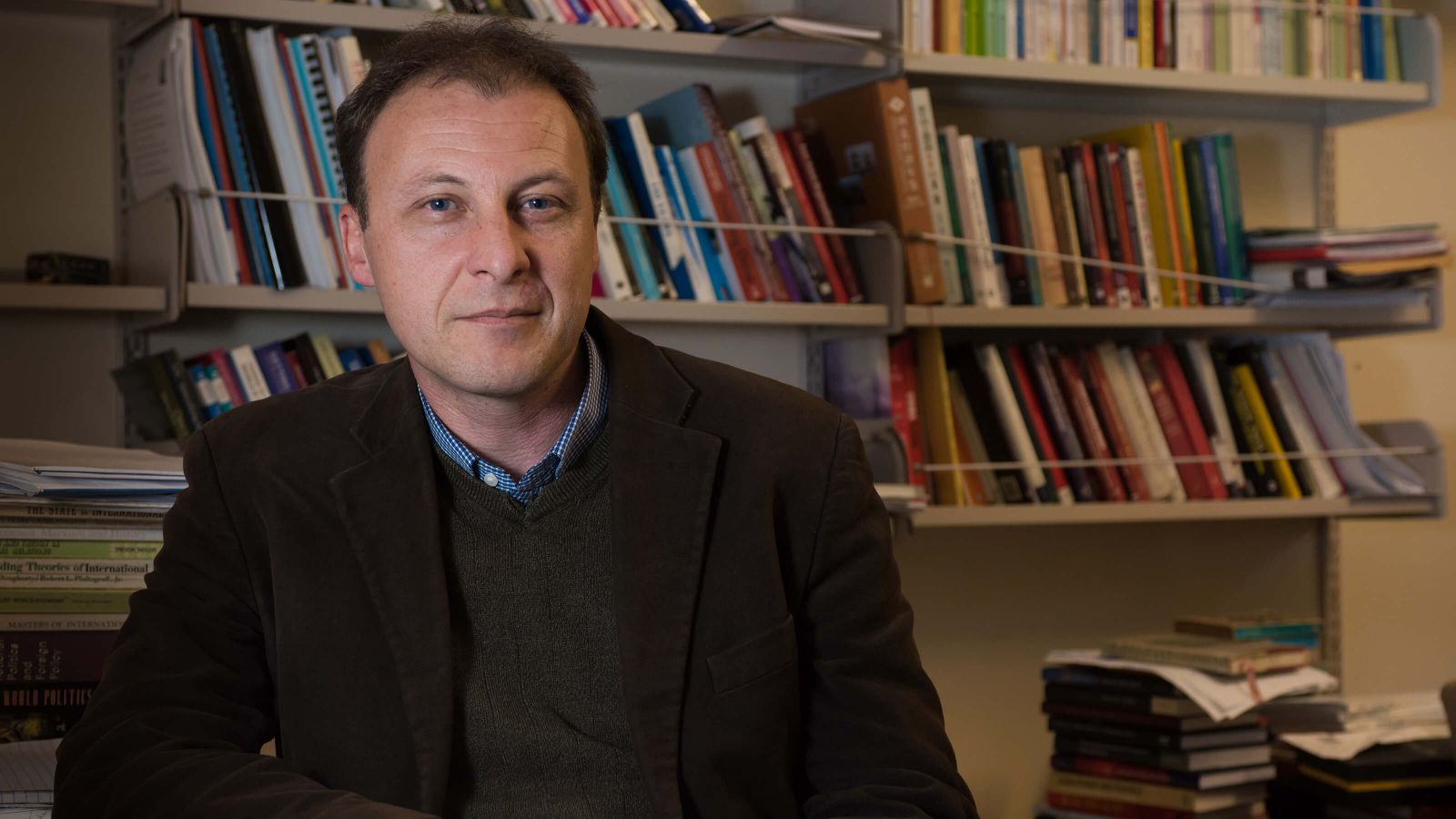

The foreign policy ‘hustler’

An expert in politics and security in the Asia-Pacific, Van Jackson has been an advisor to the US government and now shares his insights with the world.

Exploring the impact of Māori Television

The channel has contributed to political and cultural revitalisation for Māori and shaped notions of nationhood, says media researcher Jo Smith.

From dairymaids to soldiers

Charlotte Macdonald’s research has focused on the history of New Zealand women and on the troops who fought in our bloody 1860s Land Wars.

Solving real-life problems in museums

Conal McCarthy wants to do research that helps people—examining the care of indigenous objects, museum practice and the mix of Māori and European ideas.

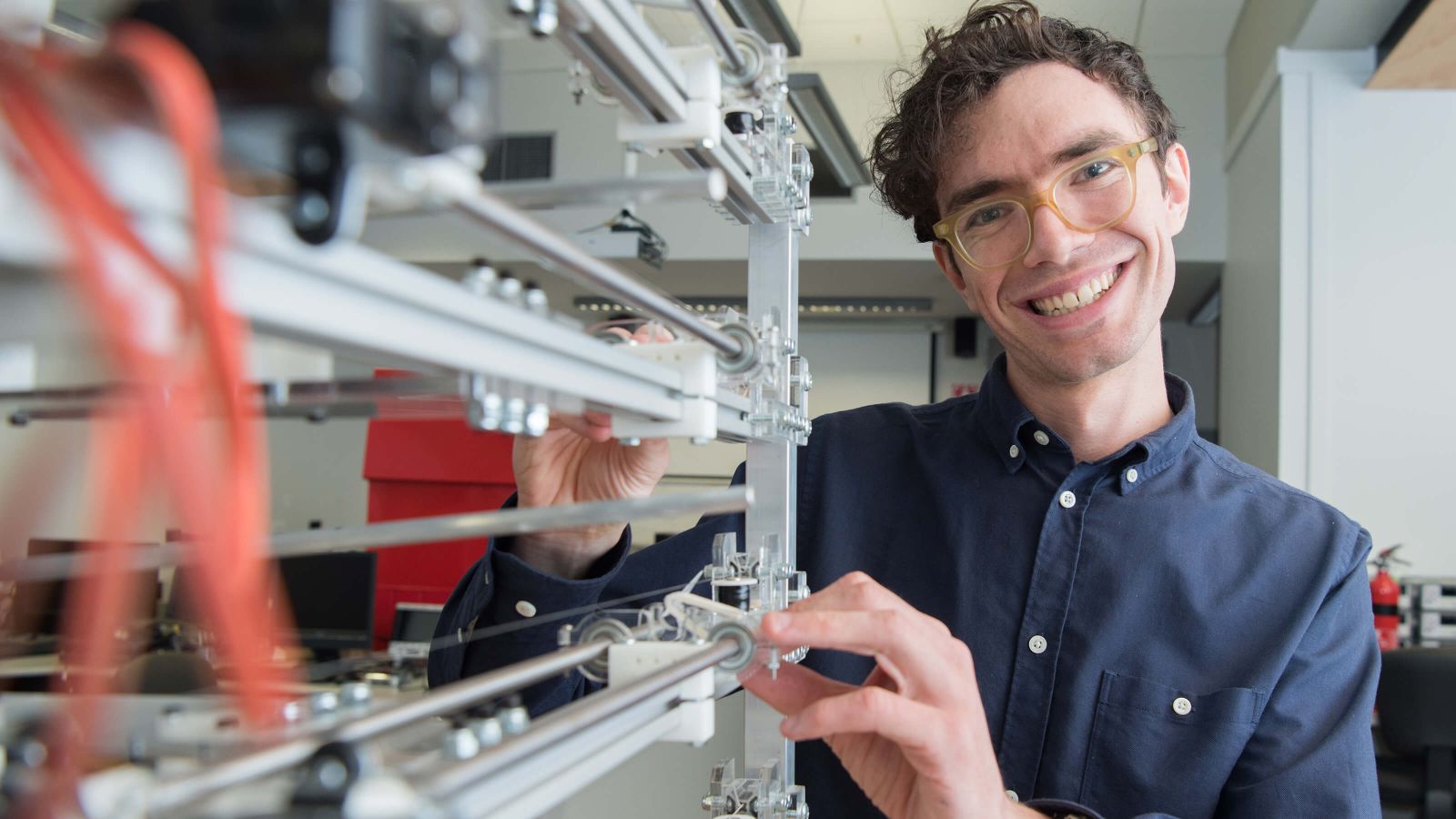

Rise of the machines

Music lecturer Jim Murphy creates mechatronic and robotic instruments that expand the universe of musical possibilities.

Living between two worlds

New Zealanders need to move beyond seeing China just in terms of trade says Jason Young, whose research aims to deepen our knowledge of the emerging superpower.