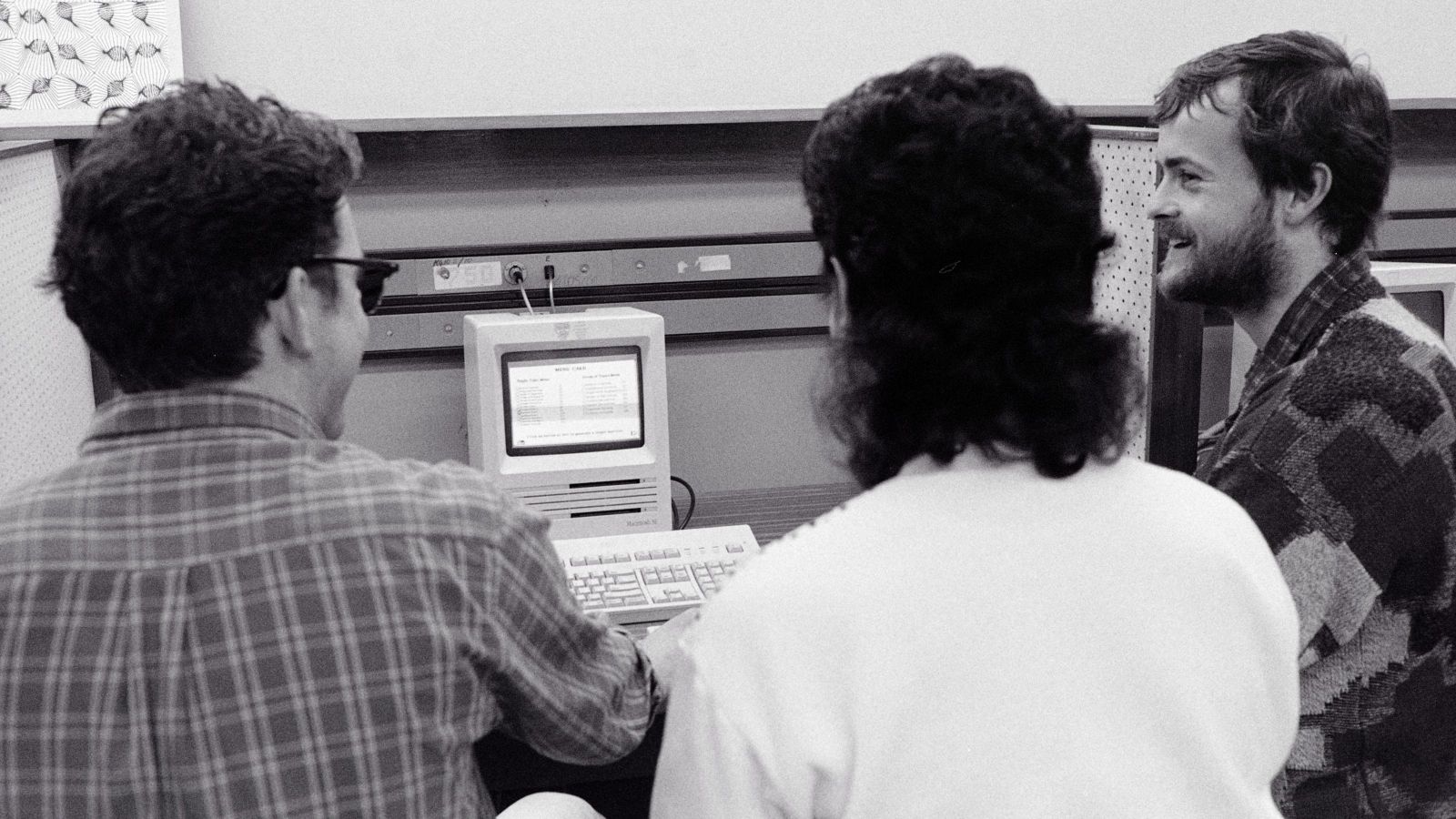

Early in 1986, Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington’s inaugural Professor of Computer Science, John Hine, connected New Zealand to email and the international Usenet service, a year after the first sustained internet network between our University and the University of Auckland.

Six years later, one of his students, Nat Torkington, built for the University what was Aotearoa’s first website.

These two architects of the internet in New Zealand never dreamt how it would come to influence people’s lives.

Tackling the tyranny of distance

Emeritus Professor Hine, an Inaugural Fellow of the Internet Society of New Zealand who retired from the School of Engineering and Computer Science 10 years ago, says the driving force for his internet development was feeling the “tyranny of distance” from family and academic colleagues on moving to New Zealand from the US in the late 1970s.

For Nat, who completed a BSc in computer science at the University in the early 1990s, the catalyst was a desire to open up access to knowledge for others.

Now chief executive of fashion retail software company Ontempo, Nat says John’s work on the internet cannot be underestimated.

“It was like building the roads. And then the World Wide Web, which I helped with, is like a freight company built on top of those―the World Wide Web couldn't do its thing without computers that can talk to each other. And it was John's work getting the computers talking to each other that was so significant.”

When John arrived in New Zealand in late 1977, international phone calls were prohibitively expensive and writing letters was the only realistic way to communicate with colleagues elsewhere.

“My light bulb went off in the first half of 1983,” he says. “I was on sabbatical at the University of Connecticut, and they had the ARPANET (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network) because they had government grants.

“I walked in on the first day and wanted to talk to a colleague at the University of Illinois. So I sent him an email and, you know, turned around to do something else, expecting a few hours wait, and it came back instantly. So we sat there and had what today nobody would think twice about―a real-time conversation.”

Connecting New Zealand

John wanted to continue his email collaboration when he came back to New Zealand, but found two problems: New Zealand had no connection to the rest of the world, and barely had connection between universities, government departments, and companies.

So he and his team set up a Unix-to-Unix Copy (UUCP) email service with dial-up connection to the United States. That became both a central exchange for email within New Zealand, and the launching point for New Zealand’s connection to the internet.

“As elsewhere, the internet was more a bottom-up, grass-roots project arising from some scientists and/or engineers, rather than a top-down project driven by University administration,” John says.

Funding for the project was seeded by the Computer Science department, the Applied Mathematics division of DSIR and a grant from the NZ Unix Systems User Group. Throughout 1986 email was free, but from March 1987 costs were returned through fees.

“Email was charged at $0.10 per kilobyte within New Zealand, $0.30 to Australia and $0.60 for the rest of the world. New Zealand users paid for both incoming and outgoing mail.

“All this was set up and operated for several years without a business plan or official approval above the Head of Department―me!”

Computer > sister for Nat Torkington

Nat grew up in Leigh, north of Auckland.

“When I was 9, my parents saved and saved, and bought me a computer. And I got the computer roughly the same time as I got my sister―a computer was way more interesting than a sister.

“Growing up here, there were no libraries, no bookstores, access to information was really limited. My parents would make a monthly shopping trip to Auckland, and we’d take down sacks of second-hand books that I'd read and swap them for new books at the second-hand bookshop.

“That was my only source of information. So I was primed to value access to information, data, books, and access to knowledge.”

A summer project from the former Computer Services Centre at the end of his first year at the University “gave me internet access”.

“I fell into the world of digitising and sharing information online: FTP sites, Archie services, and what would become the World Wide Web.”

The University had been looking for a way to put its printed calendar online, and to save money and maybe reach more people.

“John and Frank March (head of ITS) knew my interests, so the University hired me to do this when I graduated. Now, you wouldn't think twice about building a website. But back then, we had meetings where I had to show this World Wide Web was the way to go.

“It became New Zealand's first website,” Nat says.

“The University's marketing department got wind of this ‘website’ thing when we rolled out web access to everyone at Victoria.

“I got an email requesting that I change the colour of green used in the logo, and supplying a specific Pantone colour to use. I had to write back saying, ‘this is 1994, computer images can have 256 colours, and Victoria's specific Pantone colour is not one of them’.

“The Māori department got into the web early and published in te reo. Computers didn’t make it easy to write with macrons, so early online te reo had to double vowels to show length, such as Maaori instead of Māori.”

Web delightful, surprising, horrifying

They never imagined the overwhelming influence the web now has on people’s lives.

“Pretty much everything that's happened has delighted and surprised, or horrified, me,” Nat says.

“If you'd asked me in 1992, ‘would there be entire sections of the internet and the web devoted to cat pictures?’, I would have said no. And I would have been horrified if you told me that it would have been used for Nazis to find and organise each other online.”

Many things are now taken for granted, he says.

“We don’t sit around arguing about who was in what movie, or whether sausages contain nitrites or nitrides.

“It changes what you can do, and it just blows your mind that it really is the shrinking of the world. We can't imagine what it was like to have a disconnected world. But it was it was such a fragmented, isolated world before the net.”

John says today’s cheap internet costs are also taken for granted, compared with the email service which began in March 1987.

“We were charging by the kilobyte for email. A gigabyte is a million kilobytes so the $0.30 per kilobyte to Australia becomes $300,000 per gigabyte. Compare that with the typical home rate of say $75 per month for unlimited use now.”

Nat met and even married his wife Jenine online in Colorado in February 1996.

“We had two witnesses in the room with us, and all of our friends and family in the US and New Zealand were online on a real-time internet chat system called Nerdsholm. We said our vows to each other and our friend Andy read the homily. And people threw confetti.

“We said to people, ‘could you send us your record of what was said?’, because we might have missed something. The one guy sent us his record, but it included all of his private messages, including the one that said ‘well, I don't give it five years’.

“All because John Hine got us connected in 1986.”