The heather fields in Tongariro National Park are a familiar sight to locals and visitors alike—miles of purplish flowers stretching as far as the eye can see.

But this plant isn’t native to New Zealand—it was brought here in the 1900s by Pākehā settlers aiming to make New Zealand look more like their British homeland. Unfortunately, they were too successful, and European heather is now one of the biggest threats to the native flora of Tongariro National Park—a threat that will only increase as Earth’s climate changes in the future.

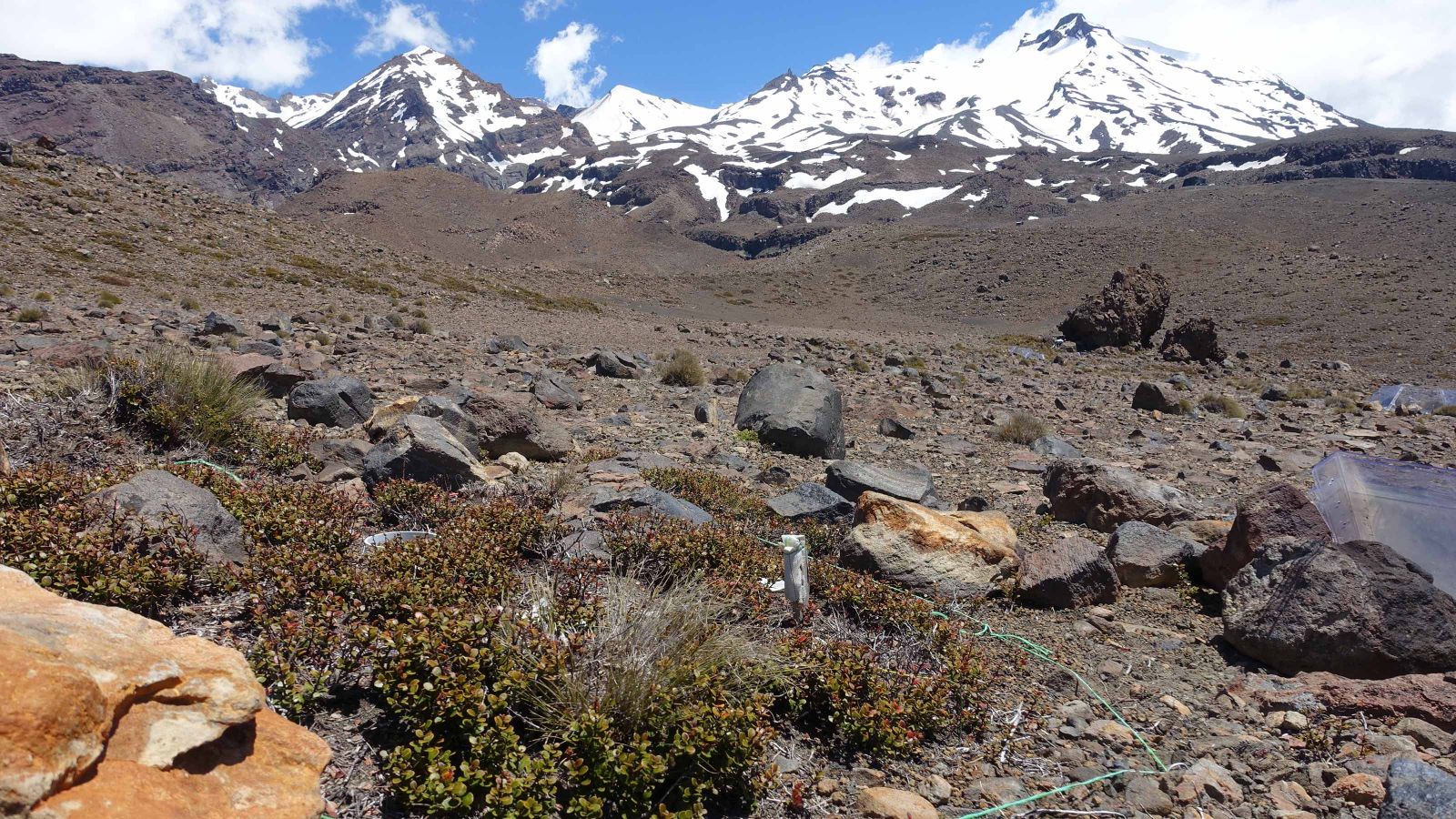

Over geological history, sea level rise caused life to retreat to higher ground. As the seas retreated, life radiated back into the lowlands from the alpine zones. Consequently, most of New Zealand’s biodiversity hot spots are now in alpine areas, including on the slopes of Mount Ruapehu, Mount Tongariro and Mount Ngauruhoe.

Today, many alpine plants are endemic to New Zealand, occurring nowhere else on Earth. We cherish our taonga, as is evident by Tongariro National Park’s unique designation as a UNESCO Natural and Cultural World Heritage site.

However, our alpine biodiversity is increasingly threatened by multiple drivers of global change, like climate change and weed invasions. These drivers can also interact, with negative consequences for native and endemic biodiversity.

Biodiversity underpins everything humans depend upon: the water we drink, the air we breathe, and the landscapes of spiritual and cultural significance.

Alongside Ngāti Rangi (a southern Ruapehu iwi), we are working to understand the interactive effects of multiple drivers of global change on the biodiversity of Tongariro National Park. Currently there is very little data available on what will happen to native plants under climate change conditions, which makes it very difficult to plan for their conservation into the future, especially as studies across the world have shown alpine areas can react very differently to climate change.

We have modelled the effects of climate change and heather growth on a selection of plants that grow in Tongariro National Park, aiming to cover as many different types of plants as possible. These plants are important ecologically and culturally, spiritually significant to Ngāti Rangi, are important components of biodiversity in the area, and some are found nowhere else in the world.

No previous studies have looked at the interactive effects of heather invasion and climate change, so our data provided new insight to how climate change will affect our native plants.

While efforts to control heather within the park are ongoing, if we do nothing to reduce the carbon dioxide emissions causing the climate to change, the outlook for native plants is not good.

Our models show an 11-fold decrease in the land area within the park unaffected by heather by 2070. We also saw a loss of suitable habitats available for all the native species we modelled, which were due both to climate change effects as well as increasing competition by heather as temperatures rise.

While the outcomes of this study might be bleak, the good news is we now have extensive data on how climate change will affect native plants. Using this data, we can make an informed decision on what we want to do to protect these plants from the multiple drivers of global change, including how much resource we will need to devote to stopping the spread of heather in the park.

There are many different existing options for saving plant life, including chemical and biological weed control, seed banks (saving the seeds of a plant in storage to regrow later), translocation (moving plants to another, more favourable location), and more.

New Zealand benefits from the political will and expertise needed to make these decisions, as well as a strong bicultural dialogue needed to ensure we make the best management decisions for New Zealanders. We can also apply our models in other parts of New Zealand, and the world, to model the effects of climate change on native flora everywhere.

Our field-based research has also allowed us to collect extensive data on features of these native plants, like characteristics of the habitats they prefer and their interactions with other plants and animals, which we didn’t have before.

In addition to the cultural, ecological and spiritual significance of these plants, we are learning that they are sensitive indicators of the health of this taonga (sacred) landscape. With this new knowledge, we have the means to educate others about these significant plants and their role in the Tongariro National Park.

As part of this project, we will be creating educational resources for children to help them learn about New Zealand’s native plants and how they can help prepare New Zealand for a future under climate change.

This article was originally published on Newsroom.