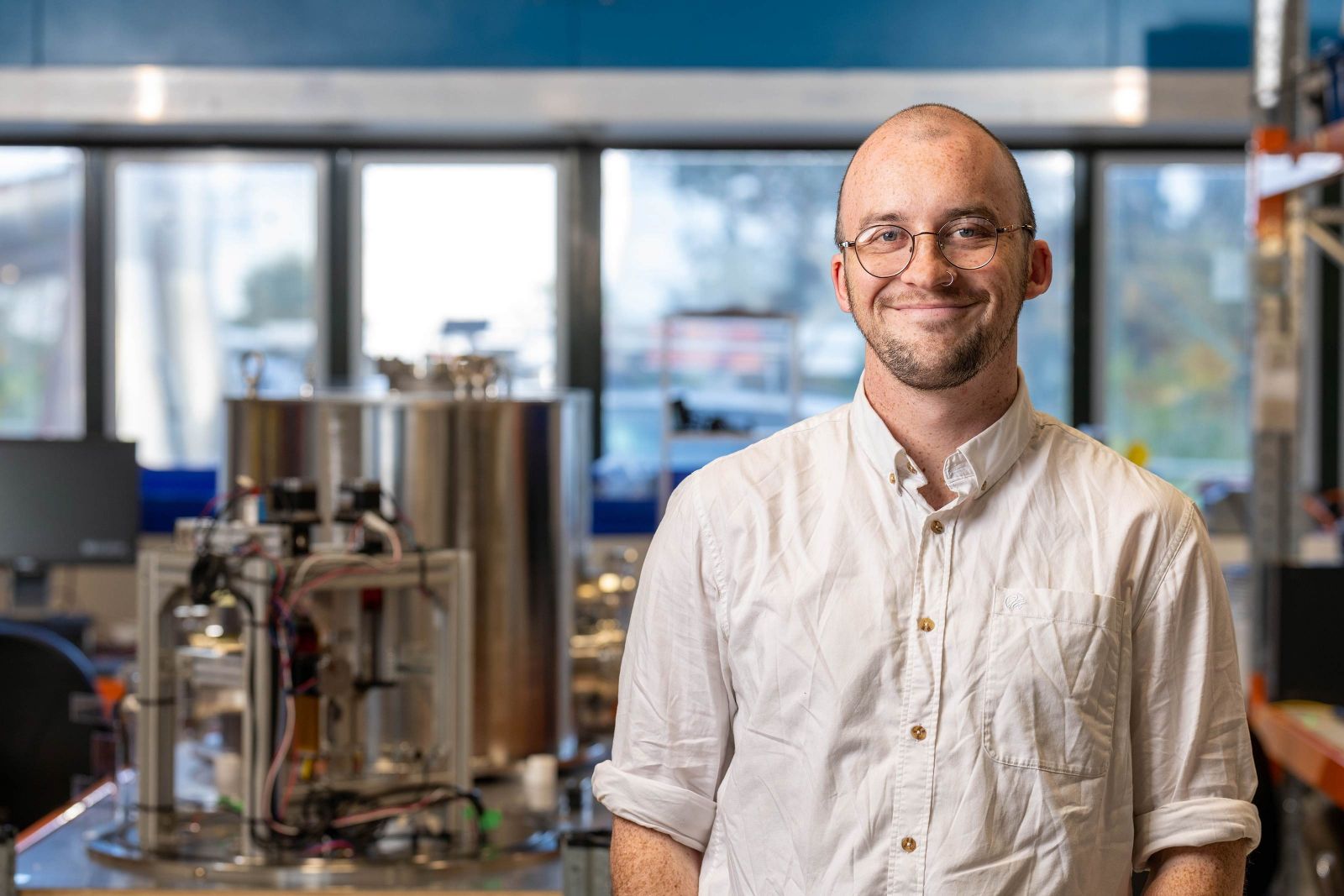

Tane’s interest in science began at a relatively young age. “It seemed like it would give me interesting opportunities and make me a well-rounded individual. I believe it’s important to try something and fail at it rather than not try at all,” he says.

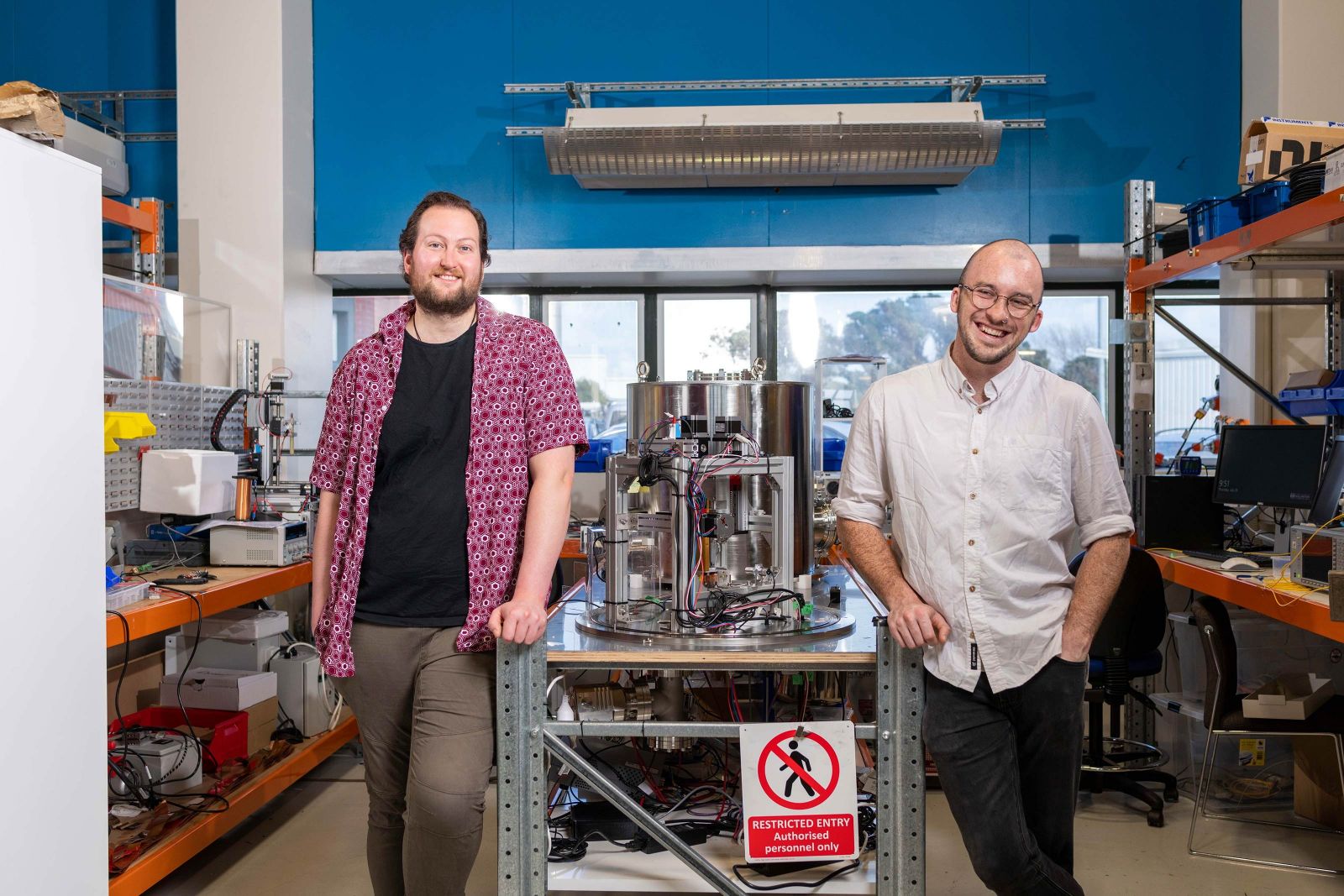

“Going to university after high school was the most obvious thing because I enjoy learning,” Gabriel says. “And being at university was fantastic, although I imagine I had a pretty stereotypical experience—I didn’t really know what I wanted when I started, did okay initially, and then got better over time.

“I really started enjoying Physics after my first year at university. You start working with others to solve problems—it’s almost quite romantic. I was pretty upset when I failed a paper in my first year, but it wasn’t that I couldn’t do it. I just had to readjust my attitude.”

Tane relates to this experience. “I did well in my first year and took on way too much in the second year. But I got things back on track in the third year. Now, I better understand the things I enjoy and I prefer the research side of things. I’m keen to undertake more hands-on research, be it with industry or academia.

“University is very different from high school—for one, some subjects end up being more interesting at university. And the first year offers students a lot of flexibility. I’d encourage everyone to try a variety of courses when they start and see what they really enjoy,” Tane says.

“People may be put off by the idea that university can be hard,” Gabriel says. “I think it’s more important to figure out if you want to stick it out. You can always ask for help. But how badly do you want to be there? How important is it that you stay the course? That attitude can make all the difference.”