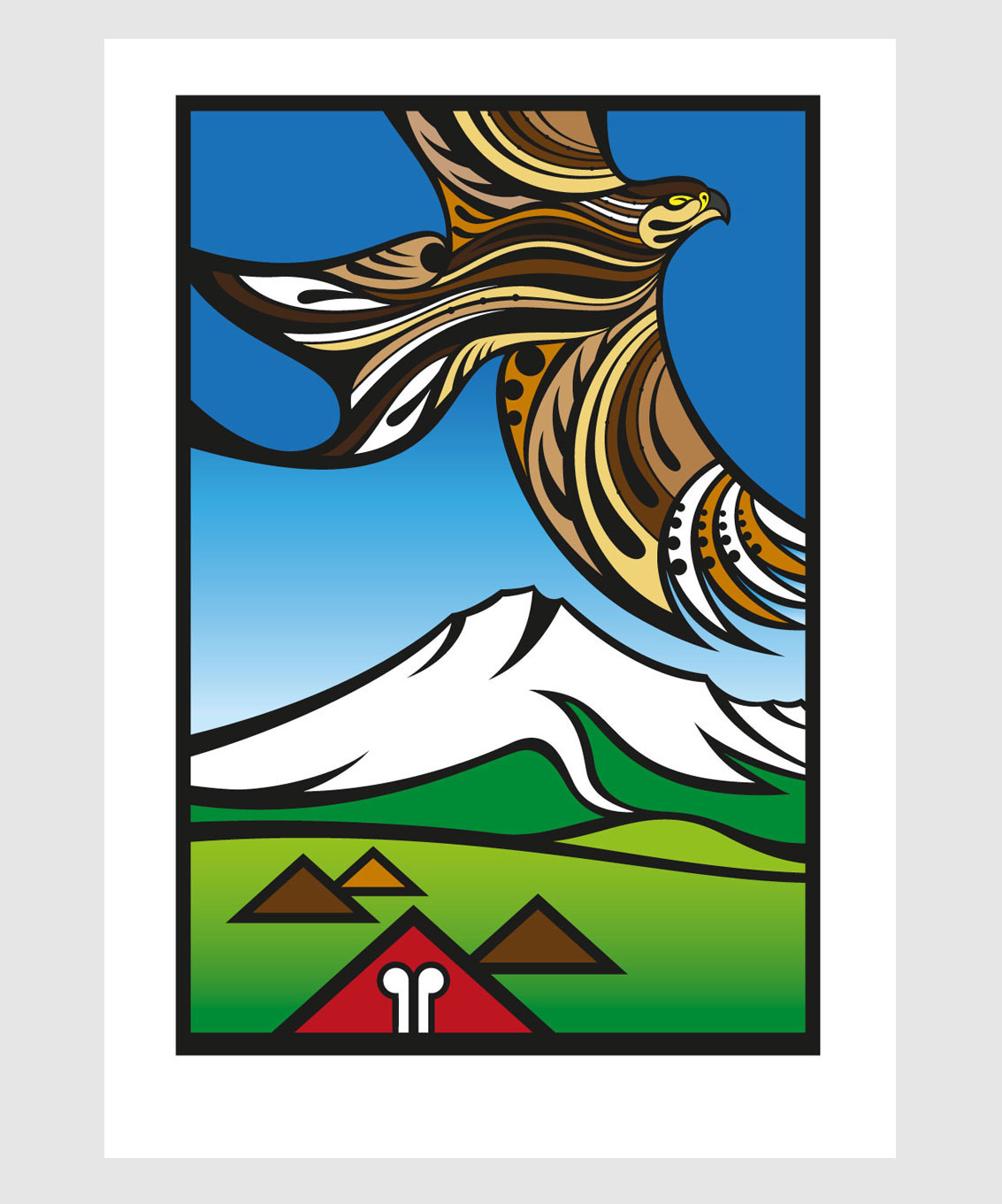

Rere ki uta Fly inland

Rere ki tai Fly coastward

Tau mai te manu The bird settles

Pītakataka ki to pae e. And flits about on its perch.

Waiata (author unknown), translated by Mitchell Ritai

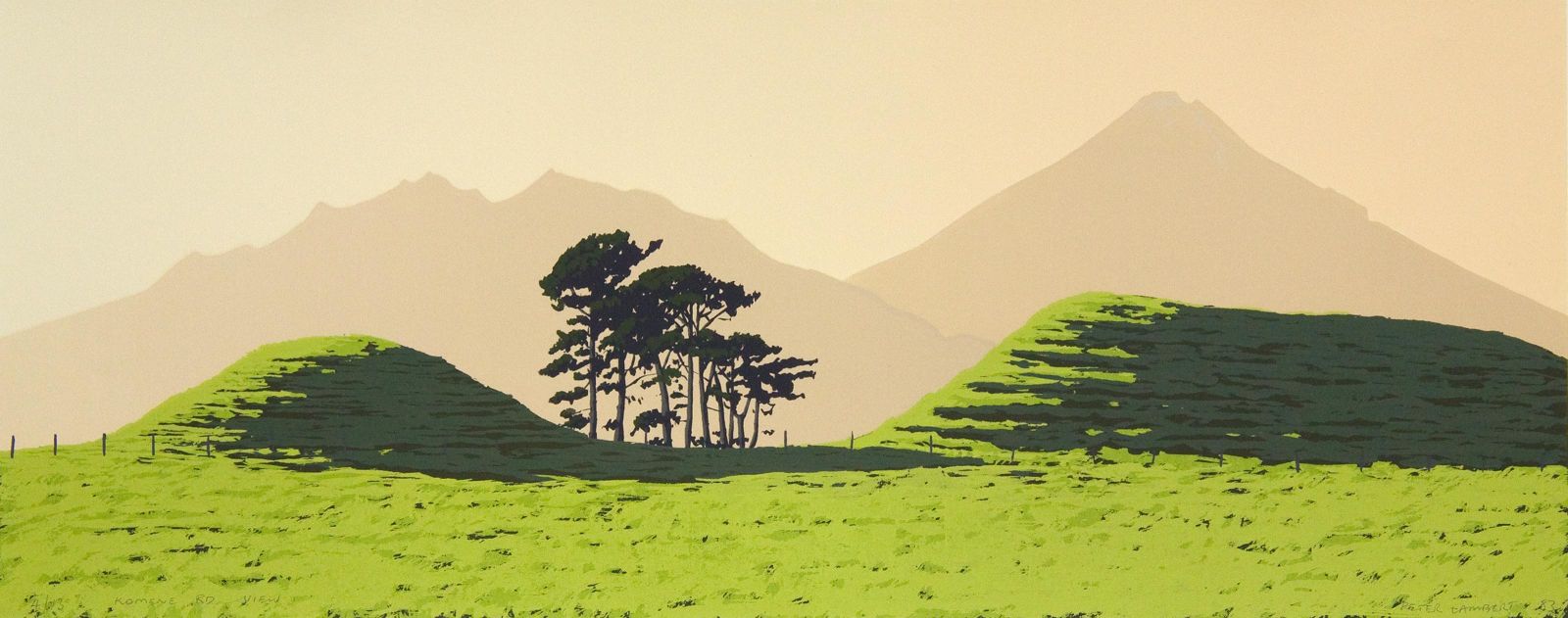

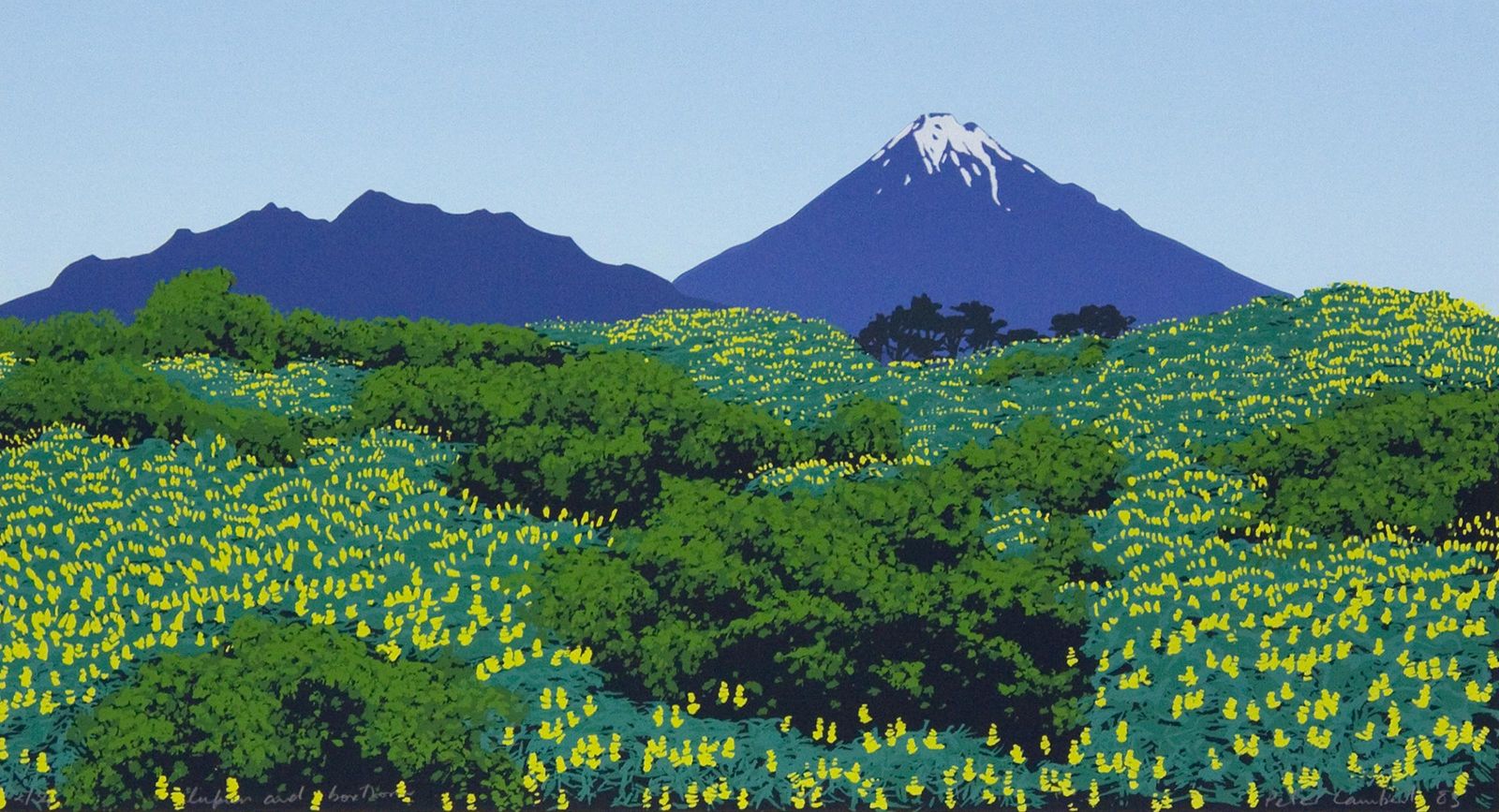

Seeking to rebuild ties to whānau, iwi, and whenua has been an ongoing story for many Māori from the time of nineteenth-century land confiscations.

Now a team of the University’s software engineers, data scientists, and humanities researchers is bringing new data analysis approaches to the task, working in partnership with Māori.

This National Science Challenge–Science for Technological Innovation project is a three-way partnership with Parininihi ki Waitotara (PKW) Incorporation Ltd, a business representing the interests of more than 10,000 Māori shareholders in Taranaki, and the University of Auckland. PKW needs to find around 7,000 missing shareholders in order to distribute more than $4.8 million in unclaimed dividends.