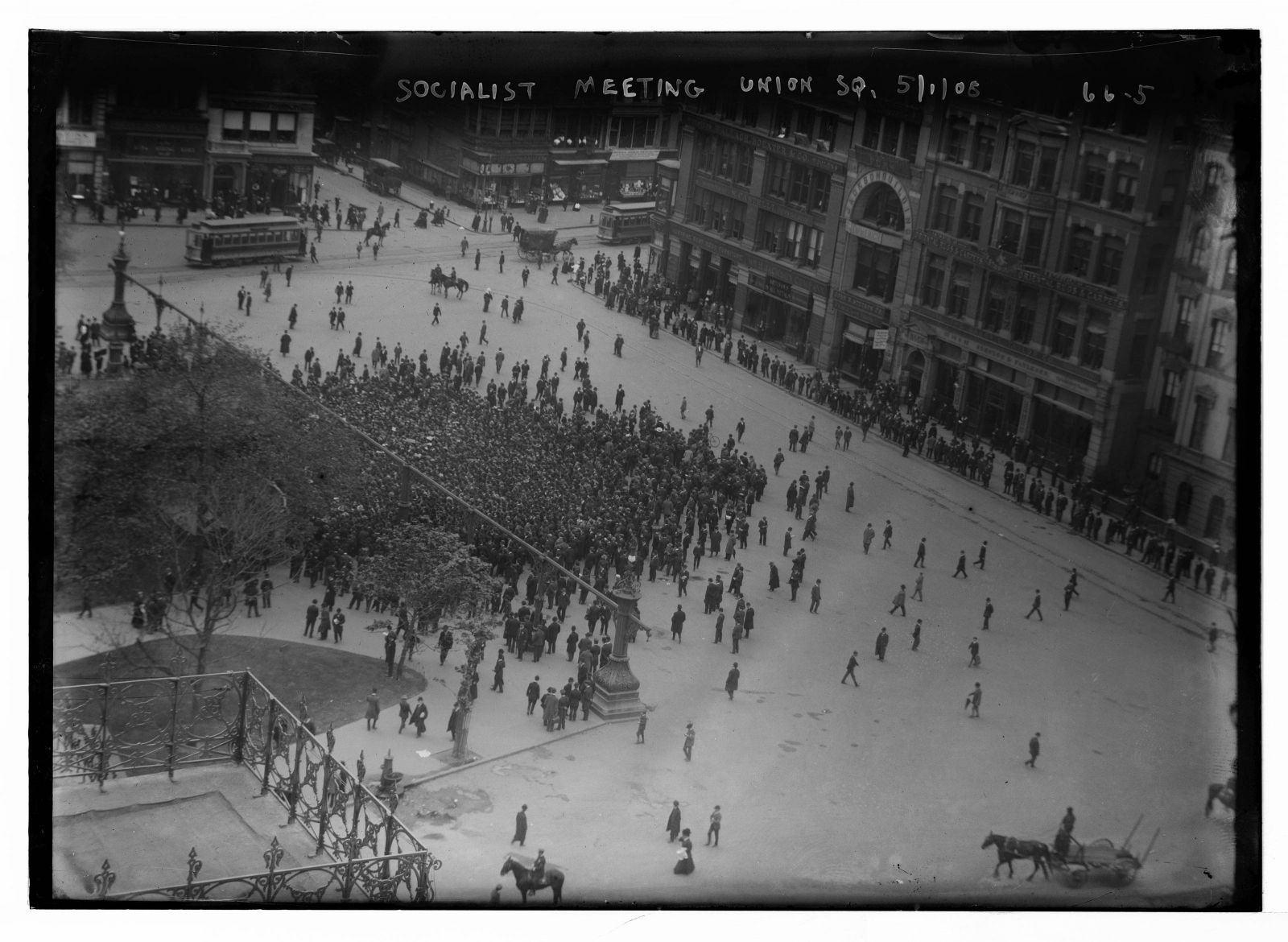

Image above: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

As Black Lives Matter protests broke out around the United States after the killing of George Floyd in May this year, Professor Joanna Merwood-Salisbury was not surprised to see one location for them was Union Square in New York.

Joanna, from the Wellington School of Architecture, is author of Design for the Crowd: Patriotism and Protest in Union Square (University of Chicago Press, 2019), a history of the square, which she first encountered when teaching at the neighbouring Parsons School of Design.

As a New Zealander, the architectural historian didn’t know about the “double life” of the square, which is on Broadway between Fourteenth and Seventeenth Streets.

Initially, she saw it as a pleasant space enjoyed by students, colleagues, and other members of the public, with a well-established farmers’ market where she bought lunch.