The Plight of Labour NGOs in Representing Rural Migrant Workers in Contemporary China

Since their emergence in the 1990s, labour NGOs operating in mainland China have played the role of de facto representatives of two-hundred-and-eighty million rural migrant workers. For more than two decades many NGOs, with varying objectives, skills, and resources at their disposal, operated with few constraints before the Chinese Government enacted the Law on Management of Activities of Overseas NGOs in Mainland China (Overseas NGOs Management Law) in 2017. This research, undertaken as a Master of Commerce thesis project In Human Resource Management and Industrial Relations at Victoria University of Wellington, explores the challenges faced by Chinese labour NGOs since implementation of this law.

Since their emergence in the 1990s, labour NGOs operating in mainland China have played the role of de facto representatives of two-hundred-and-eighty million rural migrant workers. For more than two decades many NGOs, with varying objectives, skills, and resources at their disposal, operated with few constraints before the Chinese Government enacted the Law on Management of Activities of Overseas NGOs in Mainland China (Overseas NGOs Management Law)in 2017. The law now restricts the work of foreign-sponsored NGOs in China, while other legislative measures enacted around the same time, such as the 2015 Environmental Protection Law and the 2016 Charity Law, have facilitated development and expansion of domestic NGOs. Given that foreign sponsorship is their major source of financial support, labour NGOs operating in China have been greatly affected by the 2017 law, and this in turn, has greatly influenced their goals and strategic choices when representing migrant workers.

This research, undertaken as a Master of Commerce thesis project In Human Resource Management and Industrial Relations at Victoria University of Wellington, explores the challenges faced by Chinese labour NGOs since implementation of the Overseas NGOs Management Law. Drawing on 15 in-depth, semi-structured interviews conducted from October to December 2019 with the founders, managers and activists working in 10 labour NGOs, this study examines how the 2017 NGO law and its enforcement has influenced the goals and strategies of labour NGOs operating in Beijing, Tianjin and Yunnan provinces. Seven of the NGOs surveyed in this study are located in the former, with one and two operating in each of the latter two provinces, respectively.

Findings of this research suggest that, while Chinese labour NGOs have experienced significant setbacks since the introduction of the Overseas NGOs Management Law, most remain operational, although their influence over industrial relations and public policy has greatly diminished. Despite such resilience, many such organisations felt compelled to revisit their goals and strategies and to adapt to the changed political climate to survive. To that effect, the changes made by Chinese labour NGOs to their strategic direction and desired outcomes as a consequence of that legislative change, ranged in scope from relatively modest or not at all to all-encompassing.

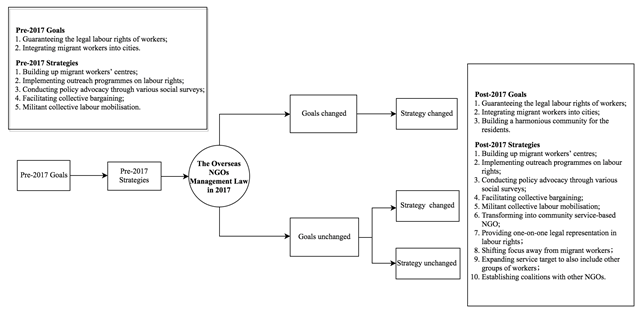

The strategies and subsequent goals pursued by these organisations both before and after enactment of the Overseas NGOs Management Law are set out in Figure 1. These fall into three distinct groups. The first is comprised of those NGOs, one located in Beijing province and one in Yunnan province, which shifted from being labour-focused to become community service-based organisations. Six of the 10 NGOs, four operating in Beijing province and one each in Tianjin and Yunnan provinces, comprise the second group of labour NGOs that maintained their labour-focused goals, but whose strategic approach to attaining those goals became less direct, more individualist and ostensibly amenable to the government's agenda. The final group, comprised of one NGO in Beijing and one in Tianjin province, did not alter either their goals or strategies. It is noteworthy, however, that both organisations in this category have been banned from operating in China since 2019.

Figure 1: Pre- and Post-2017 NGO Law Chinese Labour NGO Goals and Strategies

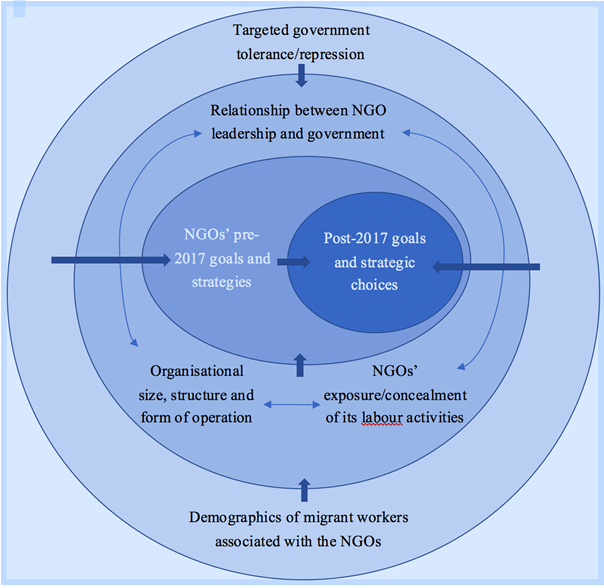

Six factors were found to have affected the post-2017 goals and strategic choices of the 10 labour NGOs surveyed (see Figure 2). Among these, two factors – targeted government repression and changed demographics of affected migrant workers – were determined to have been fundamental to the shifts which took place in that time. With regard to the former, by curtailing their overseas financial resources, the NGO lost their primary source of funding. In addition, following enactment of the 2017 Overseas NGOs Management Law, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), the country’s only lawful workers’ representative which functions as an arm of the State, stepped up its efforts to wrest control from labour NGOs in representing rural migrants. Concurrent with this, the dominant pattern of movement from the rural areas to urban centres shifted from individual to family migration, This, in turn, precipitated a reduction in the number of migrant workers being served, as well as growing concern for the wellbeing of migrant families.

Figure 2: Factors Influencing Chinese Labour NGOs’ Goals and Strategies Choice

Four other, albeit lesser, factors influencing these shifts include organisational size, structure and form of operation; the relationship between NGO leadership and government; the NGOs’ ability to conceal of their activities; and the NGOs’ pre-2017 goals and strategies. Larger labour NGOs with a more well-developed structure had a greater possibility of choosing the four new post-2017 labour strategies (providing one-on-one legal representation in labour rights, shifting focus away from migrant workers, expanding service target to also include other groups of workers and establishing coalitions with other NGOs). Those labour NGOs with a closer relationship between their leadership and the government after 2017 were more likely to change their goals and strategies after the introduction of the Overseas NGOs Management Law, and vice versa. Most NGOs studied have chosen to conceal their labour activities since 2017.

Importantly, the results of this research challenge the applicability of the main social movement theories promulgated in Western contexts, namely resource mobilisation, political opportunity, transnational advocacy network and stakeholder theory, to China’s grassroots labour movements. For instance, resource mobilisation theory, which argues that the success of social movements depends on the availability and utility of resources such as time, money and skills, cannot explain how most labour NGOs have endured in the post-2017 era, in spite of their overseas funds being restricted and the detention or expulsion from the country of most high-profile labour NGO activists by the Chinese authorities. Likewise, the fact that most Chinese labour NGOs have continued to operate – albeit often in nuanced form – under political repression belies the premises of political opportunity/process theory, which attributes the success of social movements to the presence of political opportunities. Finally, with their access to transnational advocacy networks and their overseas stakeholders severely constrained, the applicability of either transnational advocacy network theory or stakeholder theory is similarly limited.

This article is based on the recently completed Masters of Commerce thesis of Ao (Ollie) Zhou, School of Management, Victoria University of Wellington and written in collaboration with Dr Stephen Blumenfeld.